Household debt is at record levels. Mortgage stress is at record levels. Yet interest rates are at a record low. What would happen if interest rates were to rise to historic levels and predictions of 50% of Australian households suffering mortgage stress became reality? Or is high debt actually putting a ceiling on RBA rate rises meaning we need to completely rethink what “normal” interest rates now look like?

Australian household debt has reached a new record at an average debt to income ratio of 189%. The RBA’s Governor last week cited concerns that this level of debt could force households to curb spending if prices suddenly fell, bringing the economy to a grinding halt.

What he didn’t say was that the same concerns should exist if interest rates rise. In fact, as repayments don’t actually rise with falling home prices but they do with rising interest rates, there should be more concern about rising rates than falling home prices.

This question of the affordability of a rise in interest rates is something we’ve covered before the US, EU and Japan. These economies’ debts are dominated by its governments, so we looked at how much of an increase in rates could the governments cope with before the economy would be severely impacted .

.

But for Australia, debt is dominated by households. When interest rates rise, it will be household budgets that become the brake on the economy, not government. So when we are trying to forecast interest rates, it is the household sector that is the most relevant.

A lot has been written in the media lately about Australian’s level of debt. On one hand we have higher debt than almost all of our global peers. On the other hand, interest payments are lower than long term averages and household assets are also at record levels.

So what is the real situation with household debt and the ability to cope with rising repayments? We analyse this below, starting with the latest raw data and then making some observations that are relevant for forecasting interest rates.

The Data

- Leverage isn’t bad if its affordable:

- 8.7% of household income spent on interest payments, slightly below the average for the past 20 years of 9.1%

- While debt is at a record, so are asset values, passing their 2007 peak during 2016

- But leverage also means the extremes get more extreme:

- 1/3 of households have no mortgage buffer

- 24% of all households are currently experiencing “mortgage stress” (definition: income does not cover ongoing costs), up from 15% in 2011

- 52,000 households are at risk of default in the next 12 months, according to Digital Finance Analytics, an economics consultancy that has produced household financial stress data for the past ten years

Households are three times as sensitive to increase rate rises as they were twenty years ago and nearly twice as sensitive as ten years ago

As total debt to income rises, so does sensitivity to changes in interest rates.

Over the past 20 years, Australian household debt to income has risen by 80%. In that same time, mortgage rates have dropped by around 1.5%pa, and housing debt as a percentage of total household debt has risen, making interest costs per dollar of debt much lower.

The result is, as shown above, only 8.7% of household income is currently spent on interest payments, below the 20 year average of 9.1% and well off the peak of 12.2% in September 2008. At current interest rates, this is manageable. However, with so much more debt per $1 of income, households are much more sensitive to rate increases.

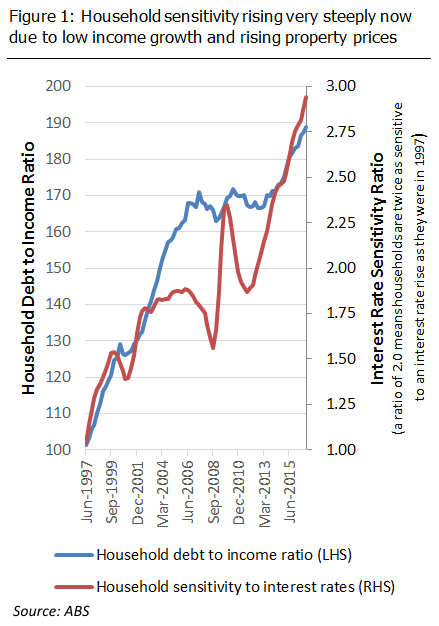

In Figure 1 we have shown this sensitivity relative to 1997. Looking at the impact that a 0.25% increase in rates would have on household disposable incomes, the lower that interest rates have gone and the higher that household debt has become, the more rapidly household sensitivity to rate rises has grown.

In Figure 1 we have shown this sensitivity relative to 1997. Looking at the impact that a 0.25% increase in rates would have on household disposable incomes, the lower that interest rates have gone and the higher that household debt has become, the more rapidly household sensitivity to rate rises has grown.

This means that the impact that a 0.25% rate rise would have had on household disposable income, and therefore potential spending by households, doubled between 1997 and 2011. A 0.25% increase in 2011 had the same effect as a 0.50% increase in 1997 (shown as an Interest Rate Sensitivity Ratio of 2.0 in Figure 1).

Sensitivity has risen by the same amount again between 2011 and 2017 as debt continued to rise, but also income growth slowed to record lows. A 0.25% increase in rates today has the same effect on household incomes as a 0.75% increase in 1997.

This is critical to understand when forecasting the future of interest rates in Australia. The RBA will only need to increase rates by 1/3 as much as they had to in the 1990s to have the same tightening effect.

The 1.5%pa increase in 1999/2000 would only need to be 0.50%pa today. Economists calling for rates to rise 2% from today’s levels are implying the equivalent of a 6% rise given today’s household debt levels; clearly not sensible policy by the RBA and extremely unlikely.

Mortgage stress will rise very rapidly if interest rates rise, making the Australian economy hyper sensitive to rate increases

Governor Lowe’s comments about the RBA being concerned that a housing market downturn would have a sharp impact on household spending, skirt around the real issue. Starting with the record high level of debt to income ratios for households is the right focus, but mortgage payments don’t rise with falling housing prices, but they do rise with rising interest rates. Record debt to income, record low income growth, near record underemployment all means that any interest rate increase will have a very sharp impact on household spending.

Mortgage stress has risen from 11% in 2000 to 15% in 2011 and then a sharp increase in the past few years to 23% in early 2017. Remembering that mortgage stress is defined as having less income than needed to cover the mortgage and household bills, that means that for a quarter of mortgaged households in Australia, an increase in interest rates will directly correlate to less spending. This is a particular worry for the retail sector, already struggling with low consumer spending and increasing digital competition.

Default risk has also risen sharply in recently years and will rise even sharper under a rising interest rate environment, something that the RBA is acutely aware of. DFA forecasts show more than 52,000 households at risk of default in the next 12 months, with 32,000 already in “severe stress”, meaning they were unable to meet repayments on their current income. This is a direct result of Australia’s weak employment market and high underemployment. When averages fall to a record low, the extreme end of the curve will be suffering disproportionately, most likely in mining, retail or manufacturing where hours worked have fallen the sharpest.

Conclusion

Current market pricing implies that the RBA will increase rates to at least 3.5%pa over the next ten years. This 2.0%pa increase would have the same impact as a 6.0%pa increase in the 1990s. The last time we saw that level of tightening was 1980 in the war of inflation, a vastly different environment than today. After the inflationary era of the 1970s and 1980s, the largest increase in any ten year period was 3.5%pa.

Based on household sensitivity being three times higher today, this suggests a more likely peak in interest rates at around 1-1.5%pa higher than today, taking them to 2.5%-3%pa. Depending upon the time it takes to reach this peak, this suggests a ten year fair value of 2-2.25%, and that current rates are 0.35%-0.60% pa overpriced.