We examine five key issues regarding China’s debt, following Moody's downgrade from Aa3 to A1 on 24 May

On 24 May, Moody’s downgraded its credit rating for the Government of China. By itself the rating downgrade means very little, but it shows confidence is waning in China’s ability to manage its rising debt burden. We have been warning of this risk for the past 18 months, as have many others, but markets have yet to consider China’s stability a serious concern.

Coincidently, this month’s Bank of America Merrill Lynch institutional investor survey showed that China’s ability to avoid a hard landing became the leading concern of fund managers for the first time since January 2016. Nervous financial markets could follow shortly.

Five key points about China’s debt that investors need to understand

1. China is not a mature economy – it is still going through massive transformation from an investment driven economy to a mature, sustainable consumer driven economy. If it can successfully make this transition, winding back investment contributions to GDP without hurting total GDP, its debt ratios are manageable. If not, China could face its own version of the GFC or Japan’s lost decades.

2. China is still using debt to extend the the country’s investment phase beyond its natural conclusion. However, China’s total debt situation is not extreme compared to the US, EU, UK or Australia. But, to understand the future impact of China’s debt situation on Australian investors, there are three main points you need to understand.

3. China’s real government debt is around the same as Greece

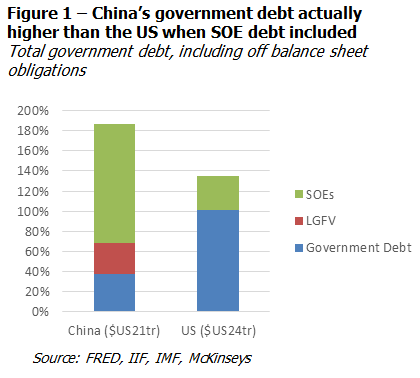

Official figures suggest Chinese government debt is much lower than the US and EU, and corporate debt much higher. As shown in Figure 1, if its state owned enterprises (SOEs) are accounted for as government debt – understanding that the likely outcome of SOE defaults will be some form of required government bailout – the numbers look very different. Regardless of the country, I prefer to look at indebtedness in this way as well as using official figures, to get a better perspective of the risk of a credit crisis.

Official figures suggest Chinese government debt is much lower than the US and EU, and corporate debt much higher. As shown in Figure 1, if its state owned enterprises (SOEs) are accounted for as government debt – understanding that the likely outcome of SOE defaults will be some form of required government bailout – the numbers look very different. Regardless of the country, I prefer to look at indebtedness in this way as well as using official figures, to get a better perspective of the risk of a credit crisis.

China’s government debt burden on this measure is 183% of GDP. This is higher than the US at 135% (101% official + 34% SOE) and is in fact around the same as Greece at 189% (177% + 12%). Obviously China has much better fundamentals in terms of cashflow and growth prospects than Greece, but it certainly doesn’t have the stability, maturity and transparency of the US. China’s headline government debt ratio of 38% is extremely misleading. In our view, it understates the challenge Beijing faces in managing the balance of credit and economic growth over the next decade.

4. Shadow banking is growing rapidly but now being managed closely

Shadow banking is credit and deposit activity that occurs off the balance sheets of the regulated banks – it includes off balance sheet transactions by banks, as well as non bank activity such as the newly created “FinTech” industry with its online peer to peer lenders.

Shadow banking is a reality for every economy around the world. China’s shadow banking is now 58% of GDP versus 86% for the US. So on the surface, China doesn’t have a shadow banking problem, but the difference is the rate of growth. The US shadow banking sector is smaller now than it was pre GFC, while China’s has grown at three times the rate of GDP at 35%pa since 2011 – moving from 12% in 2011 to 58% today. The other difference is transparency. Of the 28 countries reporting to the global Financial Stability Board’s annual review of shadow banking, China is the only one to provide select data, not all.

The good news is that the data is supported by other evidence and shows a genuine effort to reign in rapid shadow banking growth. In 2016, Chinese regulators clamped down on wealth management products, slowing the growth to near zero. From this another form of shadow banking emerged – trust companies – which have exploded by more than 100% in the past 12 months. Such is the ongoing challenge with shadow banking in any country – the ability to innovate exceeds the ability to regulate.

5. On a brighter note, China’s greatest asset is its liquidity

Most people have heard of the Chinese government’s cash reserves, which at US$3.2 trillion are more than the next 20 countries combined. However, this is small compared to the US$21 trillion in total debt. The real hidden asset for China is household liquidity.

Household wealth in China has risen an extraordinary amount over the past 30 years. Chinese households now have US$14trillion in savings and deposits.

Household debt in China is miniscule compared to the US, at 43% of GDP versus 123% of GDP respectively (Australia’s is also 123% of GDP). So the amount of spending power trapped in Chinese household accounts, which is typically saved for an uncertain retirement future, is the greatest asset of the Chinese economy. A very small amount of this stored wealth and a small reduction in annual savings equates to a massive increase in China’s GDP supported by the consumer. That is what China must achieve. The question is: how?

China’s tightrope walk

Two parallel futures exist for China. In the first one, the Chinese government has successfully navigated through the next five to 10 years, easing back investment in fixed assets and gradually convinced its consumers to spend more. In this future, household consumption is 60% to 70% of GDP, similar to other mature economies such as the US and EU. They have managed to survive the gradual repayment of SOE debt, bailing out and closing down inefficient SOEs while privatising most of the balance. Annual GDP growth declines slowly from 6.5%pa to 2-3%pa, a healthy but manageable pace for a consumer lead mature economy.

In the alternative future, consumer spending has not picked up fast enough. In its attempt to sustain investment spending at current levels to maintain GDP growth, local governments and SOEs have borrowed too much and built too much capacity, probably in sectors such as steel, coal and property. Defaults rise beyond the point that Beijing can manage, and a credit crisis akin to the GFC occurs.

Regardless of which alternative occurs in the end, the next five to 10 years will be a tightrope walk for China. They have to balance credit and economic growth until the consumer is spending enough to sustain the economy, without excessive investment spending. If they get this balance wrong, the credit crisis will set back consumer and business spending dramatically – as there is no social security safety net in China, so consumers will save for their future when stability is a concern.

Impact on Australia and how to respond as an investor

A loss of Chinese consumers’ confidence would likely create China’s own lost decade. The impact on Australia would be unprecedented. Construction, education, tourism, mining, financial services, professional services and agriculture would all suffer substantial downturns. Residential, commercial, retail and industrial property, along with equities would all suffer substantial asset price falls.

The older you are, the more you need to hedge against this risk as you have less time for your portfolio to recover. Such an issue in China would not be resolved quickly, so it is likely Australian equities would take several years to recover. Looking past the last 20 year bull market, there have been periods in the past 100 years where equities have gone sideways for 20 years or more. Such a period starting when you are at the start of your retirement years would mean that by the time markets start to recover, you have drawn down capital – therefore making it harder to recover your lost capital.

Retired investors need to build resilience into their portfolio, not just “defensiveness”. Long have the experts told us to invest in government bonds as a defensive asset, to counter equities downturns. Next week we look at why that doesn’t work in today’s ultra low interest rate environment, and why non AUD bond holdings might make more sense for you.