Over the past three weeks, our Head of Research, Philip Brown, has been touring the country providing a detailed update on the state of the Australian macroeconomy. A summary of his work is shown here.

The RBA stands at an awkward position. For the first time in my career I can honestly say that there is a clear and compelling reason for the RBA to raise rates – which I’ll outline shortly – but also a clear and compelling reason for

the RBA to lower rates too. Unfortunately, the RBA has only one tool and a relatively blunt one at that: raising or lowering the cash rate. It is a tool not well suited to controlling the sticky inflation seen in the latter part of this current fight

against inflation.

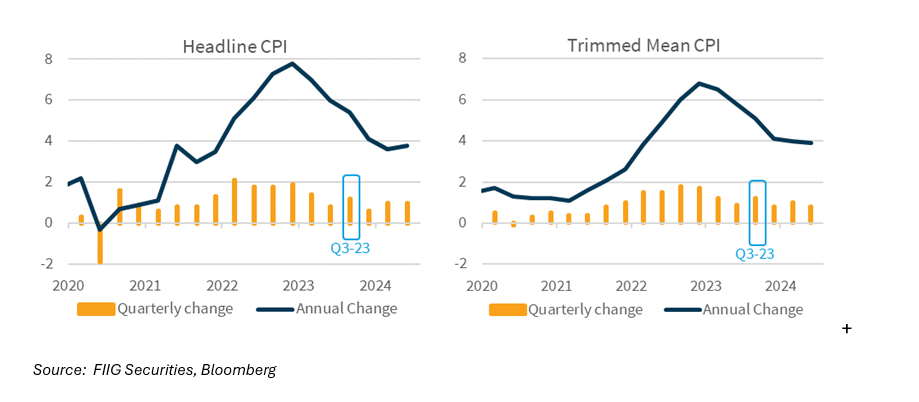

The case for the RBA to raise rates is easily made – it comes straight from the inflation data. While the inflation was not as bad as feared, the Q2 data released on 31 July showed that inflation rose 1.0% in the second quarter to be 3.8% higher

over the year. Meanwhile the Trimmed Mean inflation, which abstracts from the more volatile items, rose 0.8% on the quarter to be 3.9% higher on the year. These numbers were – ever so slightly – lower than the market had feared before

the print. Nonetheless, they are materially higher than the RBA’s mandated target of 2.5% inflation. The inflation rate is being sustained by services inflation, which is unfortunately “sticky” and tends to stay high once it has

gotten high. Also, the inflation rate, while materially lower than it was during the peak of the outbreak, has stalled. The rate of inflation is no longer clearly dropping. The RBA might need to do more to force it to drop further.

The RBA seriously considered raising rates at the August meeting – they eventually decided not to but during her post-meeting press conference the Governor openly admitted they had considered doing so. The RBA’s official forecasts were also

updated as part of the August meeting and the RBA, yet again, raised their official forecast of inflation and in doing so delayed when it returns to the target.

The RBA had previously said they had limited tolerance for delaying the return to target further, but the small rise in forecast inflation of around 0.1% proved not enough to convince them to raise the cash rate in August.

FIIG is always wary of the fact that the most recent data is still covering June for the larger and more important data series, like inflation. That means the data pre-dates the 1 July tax cuts and the increase to the minimum wage and award wages that

also started on 1 July. The combination of those two means salary earners are seeing much more in their pay packets now.

We are just starting to see data covering July come to the fore. For example, the Consumer Confidence series taken around the start of August showed an increase in measured confidence of 2.8%, to 85.0 points. That’s the second highest it has been

since April 2023. In fact, there’s a clear upwards trend in consumer confidence, admittedly though it is still low in absolute terms. The business confidence series showed an interesting result. Although business confidence fell, the reported

business conditions improved two points to +6. Early signs are that the tax cuts did see at least some improvement in the overall economic position.

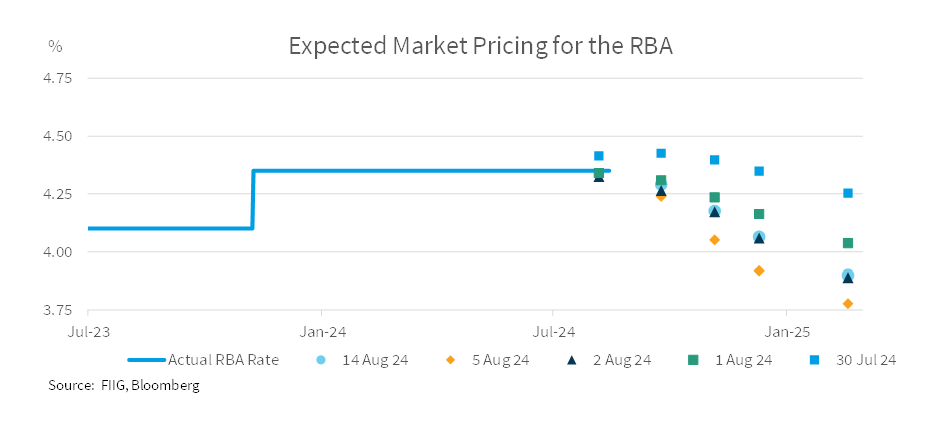

If inflation was very nearly high enough to suggest that the RBA should raise rates before the tax cuts, we’re alert to the risk that there might be a movement higher in demand from the recent cuts. The RBA seems alert to the risk too. Unusually,

the RBA Governor, on 6 August, took the step of publicly telling the market that the market pricing (which included multiple rate cuts starting very soon) was significantly more aggressive than the board’s current thinking for the trajectory

of the cash rate.

Expected pricing rose slightly, but still suggests a widespread belief that the RBA will cut rates before they raise them again. This late in the cycle everything needs to line up perfectly (or perfectly badly, depending on your viewpoint) for the RBA

to raise rates. The government utility policies will see the headline rate of inflation drop sharply in Q3, even if trimmed mean inflation remains high. That will make it difficult for the RBA to build a case to raise rates again – though not

impossible.

But if the RBA is expressly telling markets they are considering raising rates and have no intention of cutting rates for at least the next six months, why are markets still pricing in such aggressive rate cut moves? There are a number of reasons, some

better than others.

The first is that other countries are starting to cut rates or signal that they will cut rates soon. The Bank of Canada has already cut rates, as has the European Central Bank, the Bank of England and, as of today, the RBNZ. The Federal Reserve has not

lowered the US rate just yet, but the signs (and commentary) are clearly suggesting a rate cut is coming soon. We don’t think that matters as much as bond markets believe. The Fed, the BoC, the BoE and the RBNZ raised rates materially higher

than the RBA did. This was a deliberate policy choice by the RBA to hold back the last few potential rate rises so as not to risk a material rise in the unemployment rate. Other Central Banks, which used a more standard and more aggressive response,

raised rates a little higher and are now considering cutting rates. However, these other banks are implicitly – and in the case of the RBNZ explicitly – talking about cutting rates only a little: maybe 50-100bp, which would take the cash

rate in the US, England and NZ into the range of the current RBA cash rate at 4.35%.

As an active policy decision the RBA chose not to raise rates as high as they might have done, opting instead for a longer and lower peak in the cash rate. That other countries with higher rates have already reached the end of their cash rate peak and

are preparing to lower their cash rates to the level of the current RBA rate is not a strong argument that the RBA should lower the Australian rate.

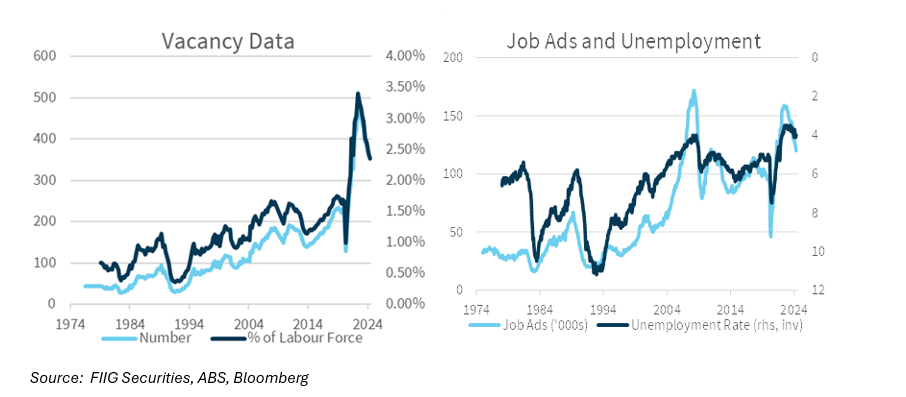

A stronger argument for lowering the Australian cash rate is that the labour market in Australia is clearly trending to the weaker side. We’re wary of commenting too directly on this series here because there will be updated data released on 15

August – likely around the time this article is distributed. So there could be serious changes immediately - however, some of the broader trends can still be identified.

First the unemployment rate remains exceptionally low at 4.1% (in the June print). It has risen from a low of 3.5% and is trending, ever so slowly, higher. The low of 3.5% was in October 2022, meaning the rate has risen 0.6% in 20 months. The unemployment

rate is shown in the right hand chart below, though note it is inverted, so it correlates with the number of Job Ads. Other measures of the labour market are much weaker, however. The number of job ads and the number of job vacancies are both well

past their respective peaks.

However, the phrase “past the peak” depends critically on how strong that peak was. As our two charts show, but the job vacancy data particularly shows, despite being well below the peak, the current rate of vacancies in the economy is also

much higher than at any point in the last 40 years, excepting the last 18 months. So which is it? Has the labour market been weakening consistently for 18 months or is it still stronger than all but a handful of years in the last four decades? It

is both. Those two statements are not mutually exclusive.

However, we are interested in the dynamics between job ads and job vacancies (both of which are falling sharply) and the unemployment (which is rising only very slowly). We think the key insight is that for a long period in 2022 the Australian labour market was operating at well above full employment. There were large numbers of job vacancies where there was simply no applicant available with the necessary skill set.

As a result, there was a large backlog of jobs waiting for applicants. Now, in 2024, we are seeing the number of vacancies fall because the new entrants into the job market are taking up the existing backlog, but new positions are not being created. As

a result the backlog of empty jobs is being slowly depleted, but the unemployment rate is not rising. However, eventually, the backlog of jobs will be done and then there will be an air pocket of sorts. The unemployment rate will likely start to rise

quite quickly, even with comparatively little change in other measures.

We don’t know exactly when the rise in unemployment will come, but the RBA would love to be able to lower the cash rate to cushion that rise before it happens. Which is why the market is thinking the RBA will turn from their current extremely hawkish

rhetoric to rate cuts in a very small amount of time. On one level we don’t disagree, we think the RBA will switch from hawkish to dovish very quickly. We just don’t think it will happen quite as soon as the market seems to anticipate.

We tend to think that the market is underestimating the influence of the tax cuts (we’ve been pointing to them since our LOCK strategy was published in February). The tax cuts are going to provide a boost to the economy in the short-term and hold the RBA at bay. But the underlying weakening of the labour market is under way and will eventually win out. The restrictive cash rate is

doing solid work in the background lowering demand. We don’t expect the RBA to lower rates anywhere near as soon as currently priced, but the medium-term trajectory is clearly for rate cuts in 2025, even though we can’t completely rule

out another rate rise in the short-term. The RBA is simply being pulled in both directions.