Historically, Australian investors have been overweight (in an asset allocation sense) to cash, shares and property. This was workable, to an extent, when term deposits in Australia were higher yielding than much of the rest of the developed world. However, with interest rates now at varying levels across the globe as central banks enter cutting cycles, this has left Australian investors searching for low risk alternatives for the defensive portion of their portfolio. This is exactly where bonds come into play.

Despite the fact that bonds are new to many Australian investors they are by no means a new asset class. Early bonds were frequently issued to fund wars or further a country’s imperial ambitions at sea. In 1694, the Bank of England was established with an initial goal of raising GBP1.2m to help England to build a navy to rival that of its perennial enemy and neighbour France.

Bond certificates were elaborate and artistic affairs (see here) with ‘coupons’ that could be clipped off the bottom and periodically redeemed for cash. In the current technology driven world the payment of coupons is a rather more streamlined process albeit perhaps lacking the artistic flair of days gone by. Personally, I think that this background is very important. It points to the fact that, whilst bonds are new to many Australian investors, they are not some new age and untested product, having been around for many hundreds of years.

Recently Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway has been in the headlines for building a monumental store of cash, selling half of its huge stake in Apple. The last reported cash and low risk investments balance was US$341.25bn. Quite apart from the size, it is the change in the last quarter that has drawn attention, with US$149.9bn being added.

Historically these giant companies have been sitting on huge piles of cash. A few years ago, technology giant Apple was hitting the headlines for its cash pile which was c.US$270bn at the time. Like everyone else I was blown away by the size of its cash holdings but unlike many others, who might have perhaps had more interesting matters to dwell on, I was also very curious as to how Apple managed and invested those funds. Was it simply kept in cash and term deposits or did they take a more sophisticated approach? It does not take a genius to work out that even an extra 0.1% or 0.2% return on US$270bn is a substantial amount of money i.e. US$270m – US$540m.

I was not at all surprised to see that Apple was actually very active in managing its funds and indeed very little was left in cash and term deposits. Given that a few years have passed I thought it was worth revisiting Apple’s approach along with that of a handful of its well-known peers. I do not think that it is overstating it to say that these are some of the largest, most sophisticated and most successful companies in the world.

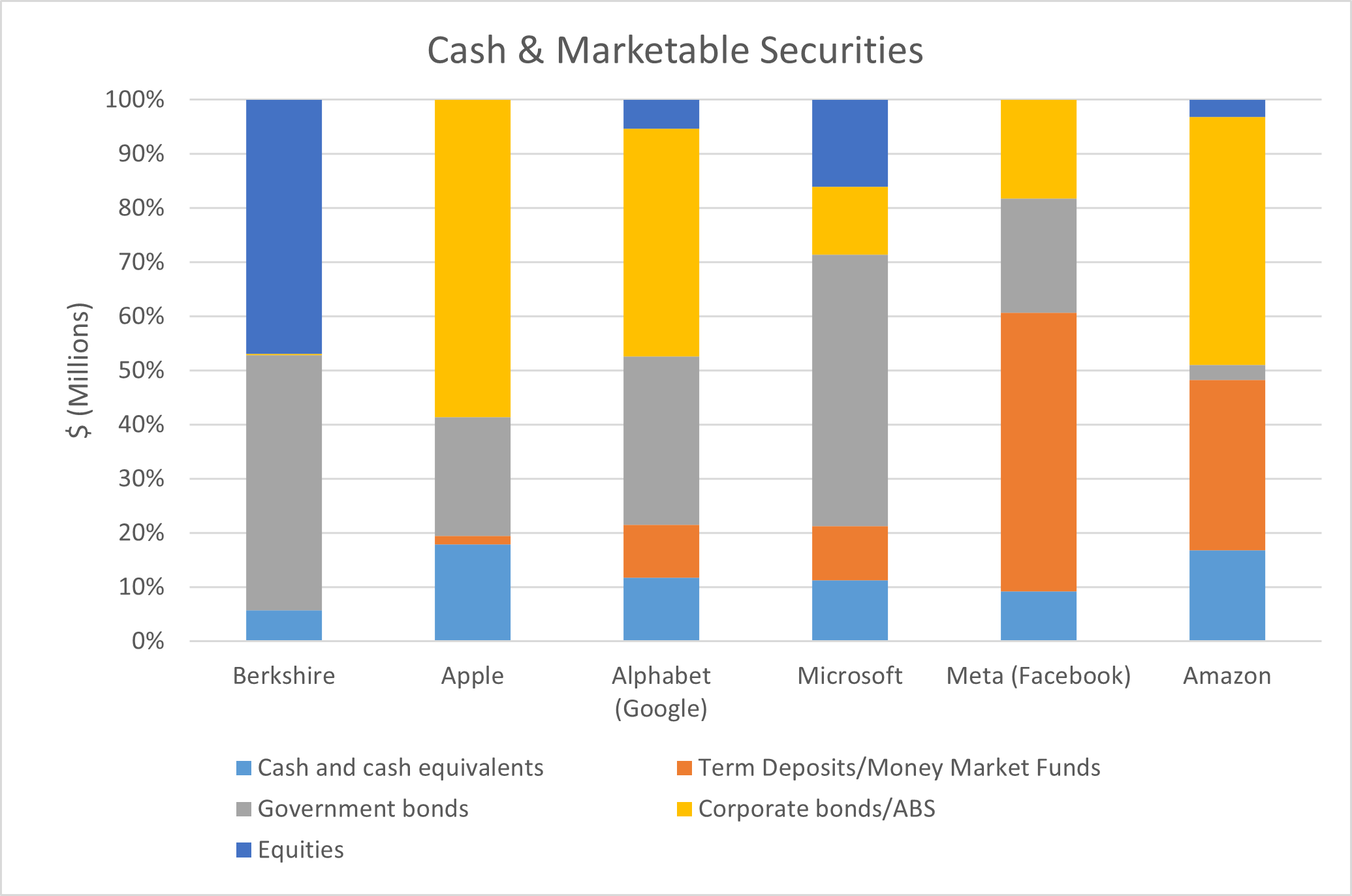

They are leading the way in their sectors and they also continue to lead the world in their cash management practices. The chart below reflects broadly how these companies invest their cash holdings. Currently these companies are each managing cash holdings of c.US$50bn – US$160bn.

To perhaps state the obvious, this is vastly more than the majority of the world’s professional investment managers have under management. However, mainstream investment managers will be managing assets across a range of different mandates from very low risk to high risk. When looking at these companies we are talking about corporate cash meaning that the mandate will always be low risk with the protection of capital paramount at all times.

Berkshire is the largest by some distance, holding ~US$634bn in total of marketable securities vs Apple next in line with ‘just’ US$151bn, but it is obviously quite different with its huge equity holdings. It is still insightful that for the vast majority of its non-equity assets it chooses not cash but government bonds.

All of these companies hold more cash as a percentage than the last time we looked, but interestingly, all hold a lot more corporate bonds than they previously did, with the exception of Meta, which has a clear preference for money market funds both historically and today.

Curiously Microsoft almost has the same allocation to shares as it does to cash. Facebook and Amazon hold higher proportions in cash and term deposits; however each still maintains vast holdings (tens of billions of US dollars) of Government and Corporate Bonds.

As stated above bonds have been around for many centuries. Even credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s, which offers oversight (of sorts) to the bond market, has been around since 1860. Such ratings consistently point to investment grade bonds, those rated BBB- or better, being the safest part of the market. While we do not have the detailed breakdown we can be very confident that the vast majority of the exposures detailed above are in investment grade bonds.

These companies have very large cash balances; however they are all still doing their utmost to extract the best possible return whilst keeping a keen eye on risk. In Australia, while allocation to bonds is growing it remains extremely low by all international comparisons. We think that if the largest, most sophisticated and successful international companies in the world are heavily allocating towards bonds then any groups and/or individuals sitting on high levels of cash should also be seriously considering the same.