With further monetary easing anticipated, bond investors will need to adjust their yield expectations to the 5%-6% range, but this doesn’t mean they need to expect returns within this range. On the contrary, bonds can achieve a higher return than their quoted yield by implementing some active trading strategies. Here we further explore ways to improve returns beyond a bond’s headline yield.

Background

Investors for the past few years have enjoyed a high cash rate, not seen since 2012, and accordingly higher yields for low-risk government bonds (and higher yields for investment grade bonds). There has been a spate of new investment grade issuance price at yields within the 6%-7% range in the last couple of years, making the asset class very attractive, for its lower risk profile and higher returns.

However, with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) set to further lower the cash rate as we move deeper into its easing cycle, it’s very likely that yields on bonds and other asset classes will also fall. Remember, though, that the yield is normally the yield to maturity. That is to say, the average yield per year if the bond is held all the way to maturity. There is some risk involved, but investors can achieve returns well above a bond’s original purchase yield if the bonds are traded prior to their maturity date.

This was evident in the FIIG returns analysis for FY25, where the median FIIG client received a 9.08% rate of return (net of fees) from owning a portfolio of bonds with average yields of 6%-7%. But how, you may ask?

Here we talk about two investment concepts, term premium and new issue premium, which when applied as a trading strategy can create portfolio outperformance.

To begin with though, we cover off the basics and discuss yield and price- which are relevant in better understanding how these concepts all work together.

Yield and price

Yield is a primary consideration for fixed income investors as it is the expected return of a bond at a given price. The yield to maturity (YTM) is the annualised return an investor can expect to receive based on the current price and the coupon of a bond, until the bond matures. Think of it as the average return over the life of the bond. Generally speaking, bonds with longer tenor have higher yields than shorter-dated bonds - this is driven by a concept called term premium, which we come back to.

As is already known, there is an inverse relationship between the yield and the price of a bond. This inverse relationship applies to fixed coupon bonds only. Floating rate notes (FRNs) do not have this interest rate sensitivity as the coupon on these securities resets on a regular basis (usually quarterly), eliminating much of the interest rate risk. As such, in this article we’re exclusively referring to fixed rate bonds.

The yield of a fixed rate corporate bond is made up of two components – a base interest rate and credit spread. The interest rate is equal to the yield of a government bond with a similar maturity, which is taken to be the risk-free rate. The credit spread reflects the credit worthiness of the issuer of the bond. As such, issuers that are unrated or rated sub-investment grade will have higher credit spreads than their investment grade counterparts.

Bonds that are longer dated offer higher yields (than bonds that are shorter dated), as they also carry higher interest rate and/or credit risk, which we further discuss.

Term premium

Quite simply, term premium is the additional return an investor demands for holding a longer dated bond. When investors provide capital for a longer term they are exposed to more risk. Since they are exposed to more risk (interest rate risk, credit risk) they demand more return. As such, longer bonds usually have higher yields than shorter bonds. This principle isn’t unique to bonds, but any kind investment that has a set maturity in the future – for example term deposits.

As a longer dated bond becomes shorter (as it moves closer to maturity), it yields less. This is because its risk also reduces - and the additional return an investor was originally paid is priced out (all else being equal, as market conditions can also impact a bond’s price- such as credit spread and base rates etc).

The yield is an average return over the bond’s life. However, a bond won’t typically provide the same return every year. Some years the return is higher than the average, and some years the return is lower than the average. Moreover, a bonds’ returns will typically be higher in its early years versus its later years, when the investor is being compensated for the additional term and credit risk.

Investors can crystalise this extra return earned in a bond’s early years by selling the bond before it matures at a price higher than where it will redeem ($100) and reinvest that capital into a new bond in the early stages of its life. This process of taking profits on bonds that have ‘overperformed’ in their early life stages, and recycling the profits into new bonds, is called rolling down the yield curve.

Rolling down the curve

Let’s demonstrate with an example, using the Pacific National 2025 bond, which was issued in 2016. This bond paid a semi-annual coupon of 5.25% and matured in May this year. As such, at issuance, it was a 9-year bond with a capital price of $100 and a yield to maturity of 5.25%.

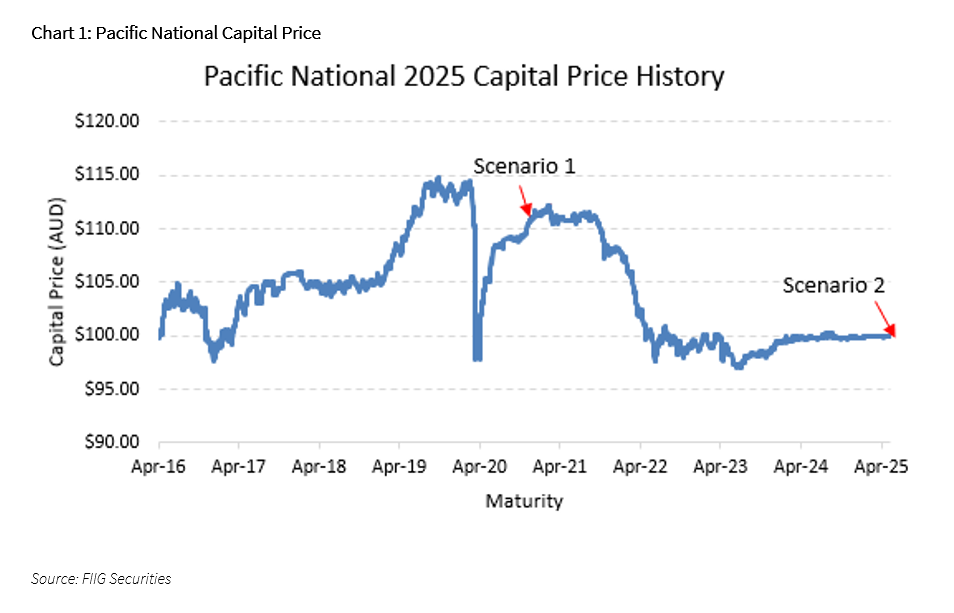

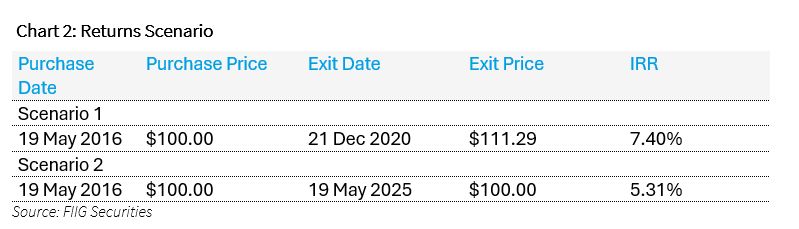

We have used the internal rate of return (IRR) to calculate the returns in two scenarios, the first scenario the bond is sold after four years (indicated on Chart 1 below) and the second scenario the bond is held until its maturity date. In both scenarios we have assumed that the Pacific National 2025 bond was purchased at primary issuance for $100.

As per Chart 2, the second scenario, where the Pacific National 2025 bond was held until maturity has a lower return (5.31%) than the first scenario (7.40%) where the bond was sold after four years at a price above the final redemption amount of $100. In our first scenario we locked in a capital gain (ie sold the bond) when its price was trading at $111.29, and its yield had decreased to 2.52% (from 5.25% at issuance). Upon selling the bond, we then could have reinvested in a new 9-year bond that was offering a higher yield. There was limited additional return to be gained by holding the bond for the remaining four years and six months until its maturity.

Notice also that Scenario 1 is not cherry picked; the bond spent a great deal of time with a price well above $100 (and so a return well above the initial yield to maturity). This vague “rainbow” shape is not a coincidence - because of the effect of term premium most bonds will be issued at 100, then spend a good deal of their life at slightly above par, then fall back towards par as they approach maturity.

This term premium argument explains the overall shape, but why does this bond do so well in the first year of its life? That strong performance in 2016 is driven by new issue premium, which is paid to incentivise investors to participate in new issues.

New Issue Premium

On average an investor is paid a premium for participating in new issues, making it more attractive to purchase in the primary market or soon after. When a new bond is issued, generally an extra spread is offered by the issuer to incentivise investors to participate in the transaction rather than buy a similar bond in the secondary market. This premium is the difference between the primary issue yield on the bond and the yield on the same bond subsequently traded in the secondary market.

There are multiple factors that will determine the size of the premium, and if there is a premium offered at all. The size of the issue, market conditions and appetite for the credit are some of the determinants.

Over the past year we’ve seen strong participation in primary debt issues, where order books have exceeded the issue size and final pricing is revised tighter. For example, Port of Newcastle’s 2033 bond had a bookbuild in excess of AUD3.2bn, raising only AUD300m and priced at asset swaps plus 220 basis points (bps) from initial guidance of 240bps.

There are many more examples of this, but the point to make is, despite pricing moving tighter, in most cases there remains a premium that is squeezed out the longer the newly issued bond trades in the secondary market. To this point, it’s worth noting that generally the new issue premium is still present as a bond begins trading on the secondary market, creating a window of opportunity before it trades away.

The Port of Newcastle 2033 bond has been issued for just over two weeks and at time of writing it has already rallied in price and yield terms. It’s currently trading close to $2.00 higher in capital price, causing its yield to have moved about 30 basis points (bps) lower. Some of that move is because of the general change in yields, but some of it is new issue premium, too.

As mentioned earlier, both market conditions and issuer-specific credit factors influence the new issue premium and how a bond performs in the secondary market. However, as a longer dated bond shortens over time, its yield typically declines creating potential capital upside. This is further enhanced if the bond was issued with a new issue premium, as the additional spread tends to tighten over time and converge with comparable bonds trading in the secondary market.

Conclusion

As the RBA is set to further lower the cash rate, fixed income investors may need to adjust to lower yields- but there are ways in which higher returns can be achieved. Through actively managing a fixed income portfolio, investors can improve their quoted yields, through exiting short dated fixed positions and reinvesting in long dated bonds and participating in new issues. It’s worthwhile regularly checking the current yields in a portfolio against when they were purchased, and a bond’s remaining tenor. This will help a bond portfolio outperform in a lower interest rate environment.

*Please note that past performance isn't a guarantee of future returns. The median FIIG client rate of return for FY25 was calculated by using client portfolios with five or more bonds and a minimum portfolio size of AUD250K, excluding managed portfolios. The median return for clients over the previous five-year period (FY25-20) and three-year period (FY25-23) was 6.62% and 8.09% respectively, based on the same client criteria from the FY25 cohort. While the aggregated returns of FY25 are lower than FY24, this is a significant outperformance of the BB AusBond Composite 0+Yr Index, which focuses solely on the Australian debt market whereas FIIG clients may have international exposure and hold investments of varying credit rating. This index returned -0.10% over the same five-year period and 3.88% over the same three-year period.