The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) raised rates last week as was broadly expected – but not everything they said was fully anticipated. They remain incredibly reticent to give guidance, emphasising the large range of possible outcomes for the next year. One more rise is quite likely, but this isn’t like the old cycles used to be. In this article we further discuss the RBA rate outlook.

Background

The RBA raised rates at the first meeting for 2026, announcing the decision to increase the cash rate 25 basis points (bp) to 3.85% on 3 February. This was largely, though not fully, expected. Although there are disagreements about how to interpret some economic numbers at present, the core observation that the inflation rate is simply too high is hard to ignore. That’s essentially what the RBA communicated.

The RBA hikes

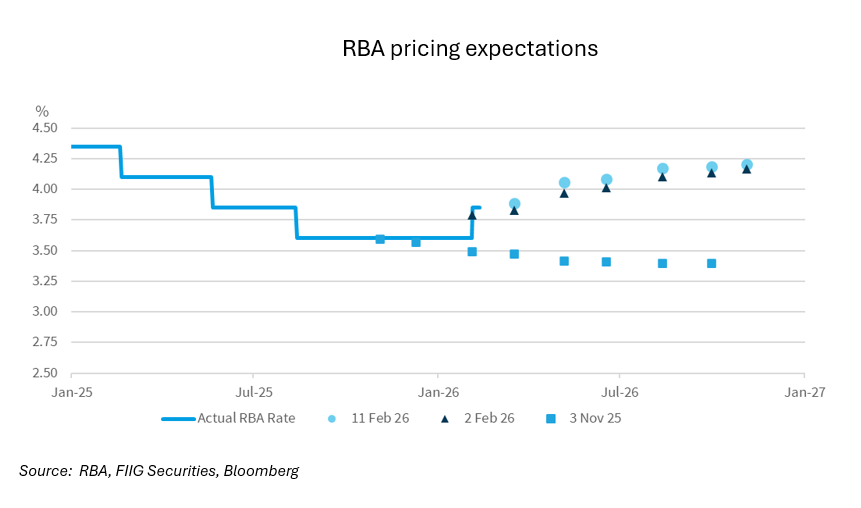

While the RBA was widely expected to hike, the market had not fully expected the rate rise, and there was a small movement higher in yields when the the change was announced. As the chart shows, this movement was there, but relatively small. Most of the movement in yields occurred well before the official announcement.

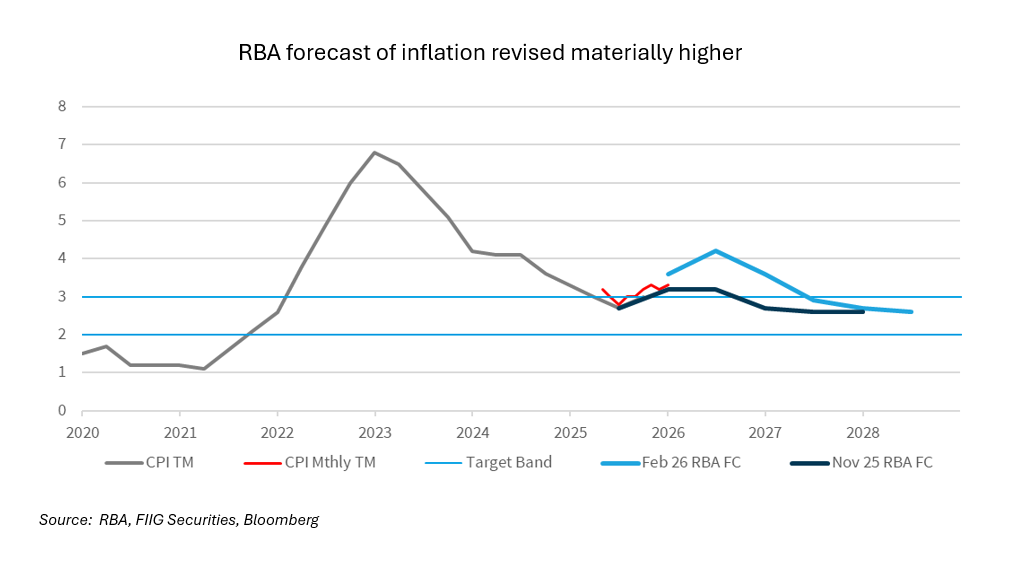

The RBA meets once every six weeks, but not all meetings are created equal. The RBA makes a complete new set of forecasts only in every second meeting. These meetings with new forecasts are the ones which occur in February, May, August and November – the forecasts are contained in the Statement on Monetary Policy (SoMP). In November, when the RBA last made these forecasts, the expectation was for another rate cut. Between November and February the outlook changed dramatically and by the time the new forecasts were released at the start of February, expectations were for a further rate rise.

The market is expecting another rate hike from the RBA by June (most likely May) with a further 10bp towards the third hike priced to occur at some point over the back part of 2026.

We quote the market pricing because the RBA no longer gives explicit guidance on what to expect at future meetings. In previous incarnations, the RBA would give forward guidance. However, after the fiasco that was the 3-year forward guidance during 2021, they are now completely unwilling to give forward guidance at all. That seems an overcorrection, but it’s where we are. Certainly, the RBA would not be losing credibility if they gave a strongly caveated weak guidance, but they prefer to remain completely mute.

There are some good reasons for the RBA’s reticence though. We are in a very different paradigm for the economy now that we’ve been any time in recent history. The lack of spare capacity means that the economy can swing from weakening to inflationary very quickly. Since the financial crisis in 2008, there has generally been spare capacity in the economy, which meant that small bursts of higher activity could easily be accommodated without any risk of inflation. That’s not true at the moment. The RBA has largely succeeded at the second of their mandates of maintaining full employment, which means there is not much spare capacity. But, in turn, the lack of spare capacity and risk of inflation means that the RBA does need to change trajectory very quickly if there is any surprise from inflation. That’s what happened in the last quarter of 2025. There was a significantly higher inflation rate than expected, which in turn caused the RBA to materially rise their estimate of the likely path of CPI, which resulted in the rate rise.

Although the inflation rate can jump quite quickly and reset rate expectations higher very fast, it is much harder for the CPI to surprise to the low side. In particular, the annual rate of inflation is affected by something called “base effects” which is simply the fact that when the next monthly CPI is released, the annual rate will be composed of 11 out of the 12 same months that are in the currently annual print. The new January 2026 result will replace the previous January 2025 monthly result, but the other 11 are already known. This means that the movement in the annual rate is really about comparing the new monthly rate to the rate from the same month one year ago. The next few monthly results to drop out of the annual window are all relatively low. There was a 0.3% in January 2025, but the next five results are all 0.2%. Unless the inflation rate drops very low, the annual rate of inflation will very likely keep rising for the next few months. It’s hard to see a material drop in the annual rate until the July 2026 results are released in August. That is why the RBA is predicting the inflation rate to keep rising from here in annual terms.

The expected upward trajectory for inflation effectively means that there is very little possibility of a rate cut for the next six or nine months unless something very unexpected (and ultimately, something very untoward) happens. But will the RBA raise rates further or not? That’s much harder to say for sure although it does look likely. Across the latter part of 2025 the data was very clearly arguing for a rate hike. Not only was the inflation rate much higher than anticipated, all the other data was suggesting that the economy was strong.

So far in 2026 the data has been much more mixed. The inflation data has been high, but the secondary data (things like consumer confidence and household spending) has been inconclusive. If the secondary data continues to weaken then the RBA might be convinced to stay their hand. However, the inflation data would need to be showing signs of weakening too. As we’ve just discussed, the annual rate of inflation won’t be falling, but the monthly rate might suggest things are improving a little. That’s why we expect a second rate rise in May.

The RBA’s reticence on guidance does make it hard to know for sure if they intend to raise rates again. We expect they do, but because they continually emphasise the wide range of possible outcomes the nuances sometimes get lost. We do suspect that the RBA will be hard to convince to raise the cash rate more than one more time.

The current cash rate is only 50bp below the peak from the post-COVID-19 years. Two more rises would suggest that the current outbreak of inflation is as serious as the post-COVID-19 one and that’s a hard argument to make. We expect the RBA will raise rates again in May (with their new set of forecasts) and continue to suggest future moves are possible. The future moves are possible, of course, things are quite choppy at present, but the market pricing already has this as a core expectation.

We discussed some of these themes in our recent Macro Outlook, named RISE. In particular, the lack of spare capacity meaning that even very small changes in the economic results be very quickly transferred into inflation. But it also means that the overall situation is very changeable. We’ve recently had a sharp change in the inflation outlook which has necessitated the RBA rate rise in February and, barring something unexpected, will likely see them raise rates further in May. In many ways, this is the price of success. If there was significant spare capacity in the economy we would not have these sharp changes in RBA outlook. But the price of spare capacity would be a much higher unemployment rate, which is not something the RBA wants to see happen.

Conclusion

Overall, the RBA needs to spend a lot more time finetuning the cash rate in the current structure of the economy. That most recent finetuning was a rate rise and there will likely be another. But the finetuning nature of the moves also means that the RBA is not trying to reverse a massive change in the underlying economy. It wasn’t a major rise in spending that caused the move, only a small one. It takes far less RBA movement to counteract a small change in the economy like we saw in late 2025 than a wholesale redirection from the economy, like we saw in previous cycles. We expect the RBA to remain nimble and reactive in 2026, but ultimately not to move the cash rate that far. This isn’t a large movement in the overall structure of rates, rather a finetuning of a cash rate that was revealed to be a little too low.