Last week’s Australian GDP data inspired two responses: 1. “GDP growth fastest in four years”; and 2. “Economic growth misses expectations”. While this might seem that the journalists are referring to different data, they are actually both correct. But one of them is really missing the point, at least as far as the majority of investors and business managers are concerned

Unless you are running a business with access to a lot of government construction spending or in the mining operations sector, there wasn’t much good news last week’s release, hence the “Misses expectations” headlines.

GDP measures the output of an economy, that is the value of the total production of goods and services in the economy for that period. The problem with this measure in Australia’s case at present is that so much of our output is dug up and sent overseas with the income flowing to a very small percentage of the population. That means that the impact on the economy overall, such as spending of that money at stores, in restaurants or with the proverbial butcher, baker or candlestick makers, is very limited.

GDP measures the output of an economy, that is the value of the total production of goods and services in the economy for that period. The problem with this measure in Australia’s case at present is that so much of our output is dug up and sent overseas with the income flowing to a very small percentage of the population. That means that the impact on the economy overall, such as spending of that money at stores, in restaurants or with the proverbial butcher, baker or candlestick makers, is very limited.

Better news is that the government is finally spending on infrastructure as that spending does tend to find its way into the economy.

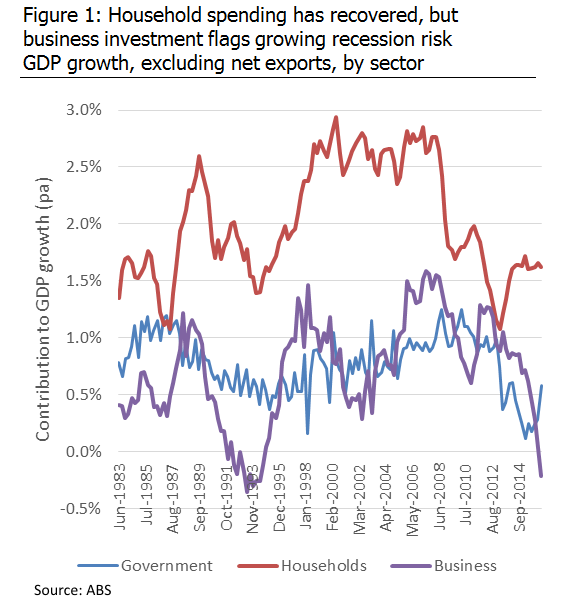

This is shown in Figure 1 which breaks down the GDP growth figure into the drivers of growth: spending by government, households and businesses. Household spending is the key driver of the economy overall, with the government sector matching business net spending, but is less volatile across the cycle.

But this driver of GDP growth still isn’t the great news that the “Fastest in four years” headline would suggest. High government spending as a proportion of total GDP is a sign of an economy in trouble, not a strong economy. And with the current government focus on reducing deficits, any increase in spending is likely to be limited.

So government spending is probably better than mining exports, but still not as good as the real drivers of economic strength: broad based business investment and of course, consumer spending. When it comes to those two categories, the news is average to awful. Consumer spending has averaged 2.1%pa, net of inflation, since 1983, and that’s precisely where it has been for the past few years. That’s up from the lows of the post GFC slump in confidence and spending, but only back to the 30 year average.

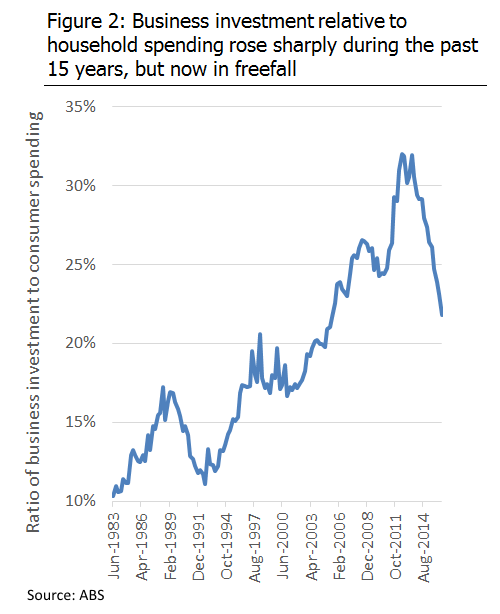

Business investment on the other hand suggests Australia is heading for a deep recession. As shown in Figure 1 above, and also in Figure 2, investment by business is falling faster than at any time since the last recession, and possibly faster. Figure 2 shows the good news within this, namely that investment is still above long term averages. But this potentially just highlights the downside risk to the economy.

Business investment on the other hand suggests Australia is heading for a deep recession. As shown in Figure 1 above, and also in Figure 2, investment by business is falling faster than at any time since the last recession, and possibly faster. Figure 2 shows the good news within this, namely that investment is still above long term averages. But this potentially just highlights the downside risk to the economy.

This drop in business investment is not just about mining investment. Over the past year, business investment has fallen in every major category measured by the ABS with the exception of computer software. Even R&D, completely removed from the mining sector and encouraged by tax incentives and the Turnbull government’s “Innovation boom” initiative, has not grown at all over the past three years.

Non residential property (eg office, retail and industrial) had previously contributed to GDP growth, but now is showing signs of weakness for much the same reasons as residential development: over-development. Vacancy rates in office property, for example, are now at their highest point since the last 1990s.

So the GDP data overall shows a mixed story. Mining output and government spending is strong; household spending is average; but business investment is very weak.

If we were investing in GDP directly, that would be the end of the story. But what we really care about, is what this means for interest rates.

Impact on rates

When it comes to interest rates, the headlines celebrating the fastest pace of growth in four years could easily lead to the wrong conclusion.

The RBA is interested in the parts of GDP growth that show indicators of demand in the economy. They lower interest rates to try to create demand when it is weaker. They cannot do anything about driving demand for exports and government spending is not typically demand driven, so these factors are far less relevant in determining interest rate movements. Business investment and consumer spending are the key factors used by central bankers in making interest rate decisions.

So, the recent trends showing rapidly falling business investment and flat household spending, continue to point to lower interest rates ahead. If demand in the economy is as weak as businesses seem to suggest, inflation will remain low. Another low inflation figure like the last and another cash rate cut will be quick to follow.