A person working one hour per week is considered “employed” and therefore not counted in the unemployment rate. We show how the unemployment rate is calculated in a simple table and explain why we still expect interest rates to be lower for longer

Avid readers of The WIRE will know that we have been calling out the misleading economic headlines for years. The two most misleading points of data – unemployment and inflation, are unfortunately also the two used most in the media to tell readers what to expect with interest rates. This probably explains why the vast majority of economists and commentators have been so poor at picking the lower for longer interest rate cycle we have experienced since the GFC.

Commentators usually report that a lower unemployment rate indicates that the RBA is more likely to increase interest rates. Headlines like “jobless rate adds to upbeat mood” and suggestions that the RBA may have to increase rates because unemployment is “so low”, aren’t quite the Trump style “fake news” – but they are still dangerously misleading.

The unemployment rate is “absurd” and “under-reported” – Geoffrey Blainey

What is wrong with the unemployment rate?

Firstly, there is the problem that the name unemployment rate implies that anyone looking for work is included. But they are not; if you have one hour per week of work, you are excluded from the unemployment rate regardless of how much work you want.

Secondly, it doesn’t count anyone that has given up looking for work. Under different circumstances this group of people could work and rejoin the labour force.

For market commentators though, it is the lazy habit of linking the unemployment rate to interest rates, when the two don’t directly correlate. The RBA’s core mission is to maximise employment, not minimize unemployment.

Combined, these points lead to the unemployment rate being used as a misleading predictor of the future direction of the cash rate. In certain circumstances, where part time employment is rising but full time employment is falling, the unemployment rate can seem positive and decline but underlying total employment also falls, as explained in the illustration below.

Illustration of why the unemployment rate is a misleading indicator of future interest rates

The two scenarios use a simplified economy that has 12 people in total. One of these is deemed too young to work (under 15) and one is too old (over 65), so its labour force is 10 people. Scenario one and scenario two describe two points in time.

| Scenario | Scenario one: seven want to work. Four want to work full time and three want to work 20 hours a week only. Of the four that want full time work, two can get full time jobs, one is working 30 hours a week and the other is not working at all. Of the three that want 20 hours part time, they all have their 20 hour jobs. | Scenario two: six want to work. Five want to work full time and one wants to work 10 hours a week only. Of the five that want full time work, three can get full time jobs, while two are working 10 hours a week. And the part time seeker can get the 10 hours they want.

|

| Participation rate | 70% (seven people out of the working age population of 10 want to work)

| 60% |

| Unemployment rate | 14.3% (one out of seven can’t get any work) | 0% (everyone that wants to work is working)

|

| Underemployment rate | 14.3% (one of the full time job seekers can only find 30 hours a week)

| 28.6% (two of the full time job seekers can only find 10 hours a week)

|

| Underutilisation rate (unemployment + underemployment) | 28.6%

| 28.6% |

| Total hours of labour employed | 170 hours (two x full time @ 40 hours each + one x 30 hours + three x 20 hours)

| 150 hours |

| Total hours of labour available to work | 220 hours (four x full time @40 hours each + 3 x 20 hours)

| 210 hours |

| Slack in the labour force | 50 hours (220 hours – 170 hours)

| 60 hours |

The unemployment rate in scenario two would suggest the RBA will increase rates or at least to leave rates alone. But scenario two is clearly an economy in much worse shape than scenario one – the RBA has less employment demand overall and 60 hours per week of extra work that could be done if businesses were encouraged to hire more people, so they should be lowering rates.

Moreover, the participation rate is falling as one person dropped out of the labour pool. This reduces the economy’s total capacity. It is harder for a central bank to influence the participation rate – but it is more likely that lower interest rates will lead to a higher participation rate – so using the unemployment rate as a predictor of the central bank’s future decisions is misleading.

Current state of employment market in Australia

The Australian economy is, of course, more complicated than this. But the scenario above is based on similar trends to the Australian economy.

Labour supply

Labour supply

- The participation rate is falling as the population ages and a greater number are over retirement age. The number of hours that people want to work is falling

- So the total labour force supply per capita is falling, meaning supply isn’t rising as fast as population, reducing Australia’s maximum capacity per capita

Labour demand

- Unemployment appears low. But underemployment shows a truer story as a lot of full time workers can only get part time jobs, or part time workers can’t get all the work they want

- Even underemployment or underutilisation fails to show the full picture as the number of hours worked per person is falling

- Total hours worked is falling further and further behind the total hours supplied

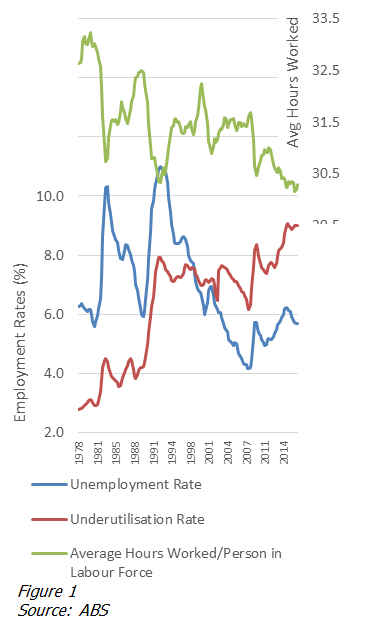

As shown in Figure 1, the unemployment rate is a good indicator of economic slowdowns in 1983 and 1992 but barely moved in 2009. This is because Australia’s labour market fundamentally changed, with part time labour a far more significant factor – particularly as Australia’s manufacturing and agriculture sectors reduced their labour demand. While tourism, education and retail which employs more part time workers, expanded. For this reason, the underutilisation rate is a much better measure of how many people are looking for work, with the total hours worked and wages growth data the best lead indicator.

Conclusion

The RBA uses interest rates to stimulate the demand for labour. They want to see total hours worked – demand –being as close as possible to total hours of labour supply, without seeing full employment push up wages, which would subsequently push up inflation beyond its target range.

Currently, inflation is far below the low end of its range, and wage growth is at the lowest level on record. The RBA should have no concern about being anywhere near full employment – they need to stimulate the economy to create more demand for labour. This means either lowering rates, or leaving them at their current low levels until employment growth returns.

Meanwhile, much of the market continues to focus on the misleading unemployment rate and therefore believes rates are heading up. Long may they continue to misprice rate sensitive investments like bonds because that will mean that they will sell bonds to us at higher yields than they should!

More detail on why the unemployment rate is far less relevant to the RBA

- A central bank, like the RBA, has a simple mission to maximise employment while keeping inflation at the target level. In Australia’s case, that level is between 2-3% pa

- Interest rates are the main tool of a central bank; they use lower interest rates to encourage more investment by business. As business investment requires employment, lowering rates leads to more employment. So the RBA’s job is to use the cash rate as an accelerator/brake:

- lower rates (push down the accelerator) when the economy needs to go faster in order to create more employment

- increase rates (push down the brake) when inflation is at risk of exceeding the target range of 2-3% pa

- leave rates (coast along with neither accelerator nor brake applied) when they don’t think it’s worth making a change

- Because of the way that unemployment is measured, a low unemployment rate does not mean high employment.If I am able to work 40 hours per week and I want to work 40 hours per week, but I can only find one hour per week of work, I am considered “employed” not “unemployed”

- Furthermore, the unemployment rate measures the number of people that can’t get one hour of work as a percentage of the labour force, which is the number of people that want to work. If the number of people that want to work falls faster than the number of people with no work, the unemployment rate can actually fall while the total number of people working falls. Unemployment is down, but employment is also down, so the RBA is not happy despite the unemployment headline

- The real measure of employment cannot be the number of people employed, but the number of hours of employment in the country as a whole. The more hours worked, the faster the economy is going

- The RBA will raise interest rates when employment is running high, not when unemployment is running low. They want to let the Australian economy grow, and therefore employment demand will grow until there are not enough people looking for more work. As a result wages start to rise, pushing inflation up.