Last edition we showed some of the background and statistics as to why we believe more Australian investors should own bonds – basically to bring them into line with global best practice in terms of asset allocation; to dampen the volatility in

their portfolios caused by an overexposure to risk assets (equities/property); and to combat the drag on returns caused by holding too much cash when it yields close to zero. You can find the article here.

In this edition’s article, we will go on to explain the basics around a bond itself, what the market looks like and how they work, so that investors new to the asset class can gain familiarity with them whilst considering taking an exposure for

the reasons in the first article.

So, what is a bond?

Very simply put, a bond is a loan.

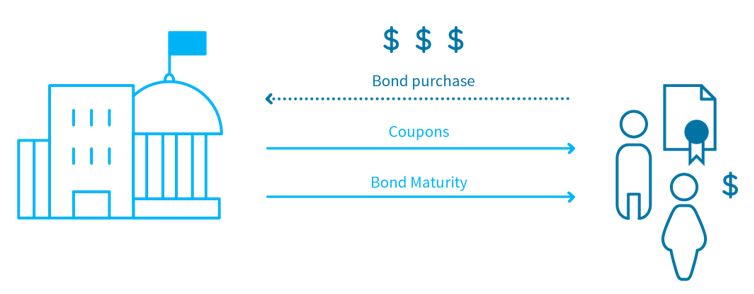

The investor buys the bond (lends) and the issuer of the bond (borrower) agrees to repay the capital at a future date, and make interest payments (called coupons) along the way. This is a very simple concept that no doubt everyone is familiar with.

At this level, bonds are not complicated at all. Some of the feedback we get from prospective clients is that bonds are very hard to understand, but when you drill down to the simplest explanation, this is it.

Types of bonds

There are 3 types of bonds, classified by the way their return is calculated. Each type can solve a different income requirement for an investor, and ordinarily we would recommend that investors hold all 3 types, as we cannot predict the future and a

mix of the three should give the best balanced outcome in terms of income and capital stability for a bond portfolio.

Fixed rate bonds

A fixed rate bond pays a fixed return for the life of the bond and is set at the time of issue. These are valuable for investors who want to know they will have a set amount of income over the life of the bond which will not vary – useful for planning

for future known expenses for example.

Floating rate bonds

A floating rate bond pays income linked to a variable benchmark (in Australia this is usually the 3 month Bank bill swap rate or BBSW).

The margin over the benchmark is fixed and set at first issue. Income will rise and fall over time as the benchmark changes.

Index (inflation) Linked

An inflation linked bond is a security linked to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or inflation.

There are two types of index linked bond:

- The capital indexed bond – the capital value of the bond changes each quarter in line with the CPI and income is paid on this inflated value, so it also changes with inflation.

- The indexed annuity bond – capital is repaid each quarter until none is left in the bond at maturity (similar to the repayment of a mortgage for example). Each payment moves with the CPI and no payment can be less than the previous quarter’s.

Market pricing

Ordinarily a loan is just between the borrower and lender and that is the end of the story. A bond however is designed as a security, and as such it is able to be traded between holders in a secondary market.

This is where some complexity can come into the picture, as the market must decide on a price for the bond so that it can be traded.

Again, this is usually simpler than expected, particularly for fixed rate bonds which have as they say, a fixed rate of return.

Here is an example of how a bond’s price can change depending on the market (all bond prices are quoted as “out of 100”, as the par value, or $100, is what is returned at maturity):

A 3-year bond is issued when the market rate for the return from this particular issuer for 3 years is 4%. The bond is a fixed rate and so will pay the same 4% coupon each year.

The first column shows what happens when an investor buys the bond in the primary issue at the very start and holds it to maturity when they are repaid. Very simple.

In the second example, after 1 year, the bond is bought by a new investor, and the market yield for this bond (now a 2-year bond) is a return of 3% per annum for the 2 years left on the bond until maturity. The coupons will still be the same at $4 per year as this was fixed at the start, but now there will only be 2 coupons received as the bond only has 2 years left to run.

To achieve a 3% yield, the investor will pay a price of $102 to buy the bond and will receive back $100 at maturity. This is a ‘loss’ of $2, but this is compensated for by interest of $8, leaving a total return of $6 over the 2 year period, which is 3% per annum. The yield to maturity calculation includes both capital and interest to show a total return over the life of the bond.

The final example shows the situation if the market requires a higher yield than at original issue of 5%. In this case, again, the coupons will still be the same at $4 per year, but the price paid by the new investor will be lower at $98. Therefore, the investor will enjoy a $2 gain plus the $8 in coupons for a total cashflow of $10 over 2 years, hence arriving at 5% per annum.

It can be a little more complex for floating rate and indexed linked bonds but the essential principle is the same – what is the market yield for the bond now and therefore what must the capital price need to be, taking into account the future income, for that yield to be achieved.

Benefits of direct bond ownership

The most significant benefit of a bond investment is that it does the one thing that no other investment can do (including term deposits in this context) – it gives a known value for the bond at a particular date in the future – the maturity date.

This is as a result of the legal obligation the issuer of a bond has – note the word obligation, which is a ‘must-do’ not a ‘can-do’ – to pay interest and capital when due.

Further benefits of this obligation are:

- Cash flow security – a stable income stream through coupons

- Capital stability – bond prices rarely move a great deal from the par value (100)

- Lower risk – than shares in the same company

Other benefits of being part of a large, tradeable market are:

- Liquidity – deep and active secondary market for most securities.

- Diversity – wider range of issuers than companies available on the stock market, plus investment away from the two most cyclical asset classes (equity, property)

The Australian bond market is a large, deep and active market, with over $2 trillion of bonds outstanding. Of these approx. $900 billion are issued by corporate issuers with a range of risk and return options to suit most investors.

Bonds are traded “over-the-counter” which means you need a broker such as FIIG to access the market, and we will also provide pricing and reporting to support your investment.

If you have further queries or would like to begin investing, please reach out to your FIIG contact.