Australia’s inflation was once largely driven by offshore inflation. But as Australia’s economy has matured, wages growth has become the primary driver – with our currency now having no reliable impact on inflation. It is likely China’s manufacturing capacity that is the second largest contributor

Inflation is relevant for investors because the RBA – and most other central banks – use it as a measure of whether an economy is growing faster than it safely can. When there is too much demand, prices start to rise more and more quickly. Too much inflation has been deemed by the central banks to be destabilising for an economy – so when there are signs of too much inflation, they tap on the brakes by putting up interest rates.

On the other hand, if inflation is too low it is a sign that supply exceeds demand by a material amount, meaning that economic growth needs to be boosted. In this case, the central bank can choose to lower rates to stimulate the economy.

Central banks don’t necessarily determine rate decisions based on inflation alone. In fact, employment growth is their objective; inflation is its measure of how much employment growth is achievable. So central banks will lower rates if they think that that will increase employment growth and also if they don’t think inflation will spiral if they do.

This means that to predict future interest rates, we must have a firm grasp on what is going on with inflation. One of the more divisive topics in financial markets, at the moment, is the future of inflation. QE was supposed to cause inflation, however economists misunderstood how “money” and the economy really interact -that’s a topic for another day. Trump was supposed to cause inflation, but doesn’t appear to have any chance of making a difference to US inflation, let alone ours.

What really drives modern day Australian inflation?

Let’s talk more specifically about imported inflation into Australia. The theory is that either protectionist governments like Trump’s will wind back global trade, causing inflation or the AUD to fall, followed by imported inflation. In my view, this is becoming accepted wisdom for why Australia’s long term rates are so much higher than cash rates, despite the absence of any real employment growth, wages growth or inflation.

That just isn’t the way inflation works in Australia. It was for some time, but around 2000-2005 Australia started to become far more self sufficient. The portion of our inflation that came from “non tradeable” items such as health, housing and education rose from 46% in 1991 to 63% in 2016. These items are barely, if at all, impacted by global trade – wages are the largest contributing factor by far.

The other 37% are tradeable items such as food, fuel, goods made in low cost markets such as China and international travel. For these tradeable goods, the combination of global inflation and the AUD currency value is the major contributing factor, but the relationship is not as obvious as the relationship between wages and non tradeable items.

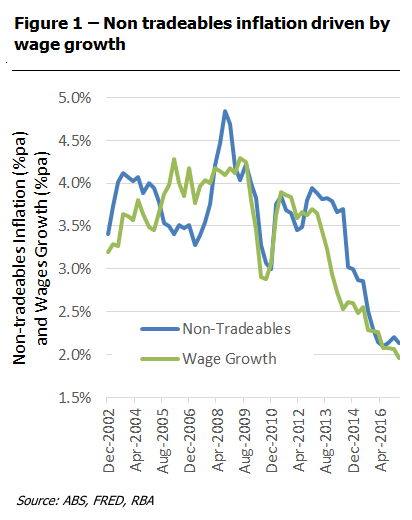

Figures 1-3 show this in very clear terms. Figure 1 shows a high correlation between non tradeables inflation and wage growth. This chart supports the view that wages growth drives the bulk of 63% of Australia’s CPI today.

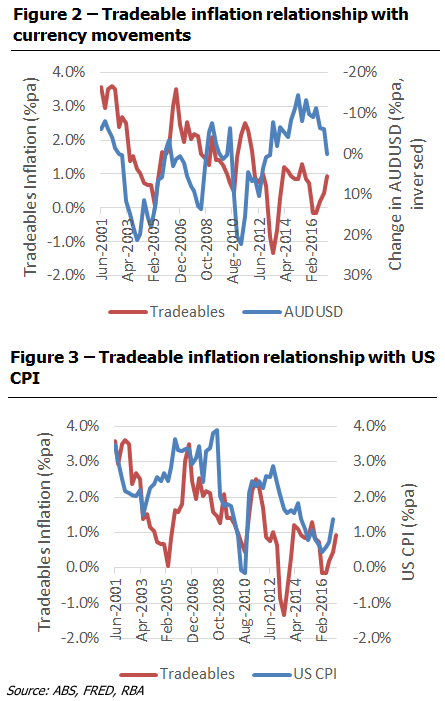

Figure 2 is a little more complex as we need to flip the AUD:USD chart upside down – it is a fall in the AUD that is supposed to cause tradeables inflation. Lastly, Figure 3 shows the relationship between US CPI and Australian tradeables inflation.

The currency link to Australian tradeables inflation is not consistent and has substantially weakened over time. On the other hand, US CPI and our tradeables inflation do appear to have a reasonable correlation.

For those more technically minded, the correlation between the data in Figure 1 is 0.53; Figure 2 is 0.10; and Figure 3 is 0.48. We see wages drives non tradeables inflation, global CPI drives tradeables, and currency isn’t a reliable influence.

For those more technically minded, the correlation between the data in Figure 1 is 0.53; Figure 2 is 0.10; and Figure 3 is 0.48. We see wages drives non tradeables inflation, global CPI drives tradeables, and currency isn’t a reliable influence.

Two thirds of our inflation is non tradeables inflation, and is driven by wages growth. The relationship is extremely close. So unless employment growth turns around and starts to grow again, this will not be a source of inflation for some time.

That leaves tradeables. If we are to have any hope of inflation, it will depend on global price inflation. Looking closely at US CPI data, the relationship between US household goods, clothing and other discretionary items, and Australian tradeable inflation was particularly high – suggesting that globally traded “made in China” type items are the common driver of both US and Australian inflation. The link between US health, education, other wages driven items and Australian tradeables inflation is extremely weak, reinforcing this conclusion.

Tradeables inflation most likely linked to China’s cost of production

Tradeables inflation could rise if China decides to cut back industrial production capacity – a plausible idea, given its high debt ratios in the industrial sector. Lower capacity in China would push global prices up. Also, a reduced industrial production capacity lower imports of raw materials and push down commodity prices and the AUD – causing tradeables inflation to rise further.

However, tradeables inflation is still only one third of total inflation in Australia, regardless of global industrial capacity, commodity prices or the AUD. We simply don’t buy that much overseas.

What about our CPI?

Wages growth is at record lows and falling. For Australian CPI to exceed 2% pa, tradables inflation needs to rise to 2-3% pa from its current 1%. Given that the RBA uses core CPI – which ignores fuel and other highly volatile items – this leaves clothing, furniture, vehicles and technology, all of which face severe downward price pressure globally.

Conclusion

At the moment, the argument for high Australian inflation requires that either wage growth stages a dramatic comeback, or prices of imported items like clothing and technology rise at 4-6%pa; enough to make up for low non tradeables items.

While the Chinese will likely lower steel making capacity, they are unlikely to ease up on their capacity for household items – so this sort of change in the global economy is unlikely.