We consider the RBA has little option but to cut interest rates given the employment market is much weaker than the headlines suggest, particularly exposing some highly vulnerable sectors of the economy

Unemployment rose from 5.7% to 5.8% in June, but this tells us very little in terms of the health of the economy. A stronger economy should be measured by the amount of work done, not the number of people not working. The reasons we care about the reported unemployment rate are largely social, but the figures are misleading for use in investing.

For regular readers, you can probably skip this quick explanation, but for others, here’s why “unemployment” is misleading and not as relevant as other measures to investors:

- Unemployment is the measure of the number of people looking for work but not able to find any job of 10 hours per week or more.

- If I have a job working 10 hours per week or more, I am considered “employed”, regardless of how many hours I can, need to, or want to work.

- So, if every person in the labour force were employed for say just 20 hours per week, the unemployment rate would be zero, regardless of the social or economic impact.

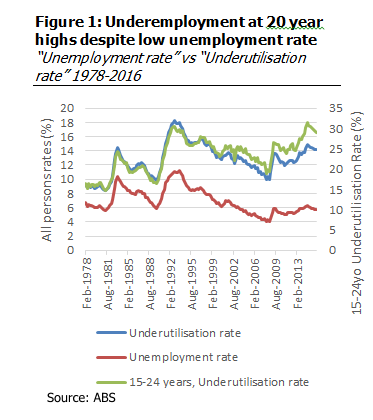

- A better measure than “unemployment” is “underutilisation”, which measures the gap between how much someone is working and how much they want to work. Someone working 20 hours per week but wanting to work 40 hours will not show up in the “unemployment” rate but will show up in the “underutilisation” rate.

- Therefore “unemployment” does not tell us how strong the economy is; the hours worked and underutilisation does.

- Given that the RBA’s mandate is maximise employment without exceeding the target inflation range, they will favour lowering rates when they feel that hours per person in the labour force is weakening and underutilisation rate is high and inflation is not at risk of exceeding their 2 to 3%pa target range.

As shown below, Australian hours worked has flat lined over the last nine months. This is not a crisis in any sense, but it is also not the rosy picture painted by the headlines.

What’s more, the issue at hand for the RBA is that since the end of the mining boom, Australia has only created about half the employment required to match its population growth.

Labour force report key points

Headlines:

- Employment rose by 0.07%, below the rate of population growth (~0.11% per month)

- Unemployment was marginally higher at 5.8%, largely due to a fall in part time employment

- Monthly hours worked fell 4.3 million hours to 1,640 million hours

- Underutilisation is not measured monthly and was last measured in May 2016, but adjusting for the hours worked is indicatively 14.3% of the labour force, its highest rate since the 1990s

Underutilisation and hours worked analysis:

- While Australia’s unemployment rate is below its long term average, the underutilisation rate is well above, and is at its highest point since 1997

- Youth underutilisation has been at record levels over the past two years, as shown in the green line in Figure 1 adjacent. Underutilisation in this age group has closely tracked the population up and down, but since the GFC its decline has accelerated

- Hours worked per person in the labour force have fallen 5.1% in the past ten years

- This means that if every working Australian still worked the same average hours as they did ten years ago, Australia’s unemployment rate would be 10.6%

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we should not celebrate the creation of the part time jobs that are responsible for lowering the average hours, but it does mean that Australia’s utilisation of its labour force is falling far behind its potential. This in turn should push the RBA to ease, all other things being equal.

Employment growth versus population growth:

- Hours worked has failed to keep up with population change in all but NSW since the end of the mining boom. Australia’s 15 to 64 year olds (working age) population has grown by around 5.2% in that time, but hours worked has risen by only 3.6%.

- In the past two years, this gap has widened, with hours worked growing by only around half the population growth rate, as shown in Figure 2 adjacent.

- Contrary to the headlines, it is South Australia that has suffered the most. While SA’s population growth is very low; hours worked has fallen a massive 4.5% and has failed to ever pass its pre GFC peak. The SA economy is the only economy with a major reliance on both mining and manufacturing; with SA particularly hurt by the winding back of its automotive manufacturing sector.

- SA also has the largest gap between employment creation and population growth, followed closely by WA.

- QLD has lost total hours worked in the past two years, but has fared much better than the other mining states as it has a more diverse economy and benefited from the east coast construction boom. That could decline in the coming months as Brisbane’s building cycle peaks.

- Victoria has experienced considerable employment growth, in terms of the hours worked, but population change has been higher in Victoria than any other state as workers return from the mining states.

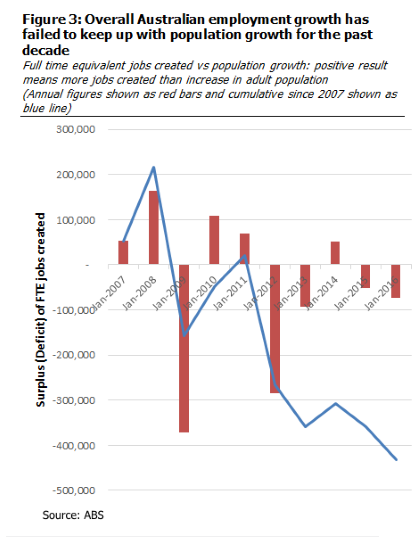

As a final point, we look at how Australia as a whole has fared over the past ten years, in terms of employment creation versus population growth.

Figure 3 shows that there has been a total of 431,000 full time jobs shortfall in the past ten years.

That is, if Australia were to have the same amount of work per participant in the labour force and keep up with population change, we would have needed 431,000 more full time jobs to maintain its unemployment rate.

Instead, we now have the same unemployment rate but the average person is working 5.1% less than they were. That is not an economy reaching its full potential.

Conclusion

The RBA’s mandate is to maximise employment while keeping inflation within the target range of 2 to 3%pa. Despite the seemingly strong performance suggested by the unemployment rate, the underlying data from this Labour Force report, and from the past three to four years, shows that Australia’s employment is far below its potential growth and so needs stimulus. Inflation is clearly well below the target range, so that stimulus will likely come from the RBA in the form of rate cuts, particularly if the global headwinds continue to threaten Australia’s economy.