Like Japan and Korea before it, China has achieved miraculous economic growth over the past forty years. All three countries have benefited from the economic catchup that tends to occur when certain structural and policy barriers are removed

Sometimes called “convergence”, the catchup phenomenon is intuitive: remove the barriers that close an economy to external capital or that prevent domestic growth, and investment capital will enter the country, fueling a sustained period of growth.

This capital will continue to flow on the promise of higher profits as new technologies and cheap labour combine. But the technology and labour cost gap eventually closes enough to slow the profits and therefore the investment capital.

When this happens, the economy is said to be “in transition”; referring to the transition from being an investment driven economy to a consumer and services driven economy.

In this transition phase, governments need to target higher personal incomes and lower economic volatility. Higher personal incomes will drive the consumer economy, and lower volatility will attract the next, more patient wave of investment capital.

Lowering volatility is challenging as the temptation for governments is always to try to keep the investment phase going, allowing debt ratios to creep up to fund the investment beyond its natural conclusion.

Japan and South Korea fell into the debt trap

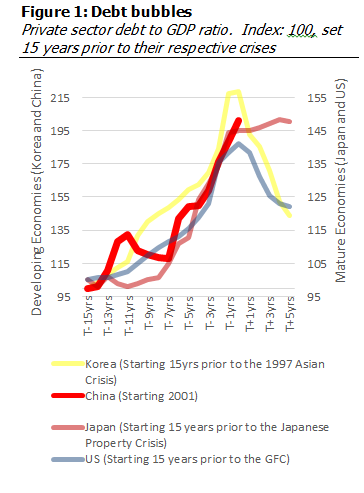

This is where both Japan and Korea got the transition wrong. Figure 1 shows the ratio of private sector debt to GDP ratios for Japan and Korea for the 15 years leading up to their respective crises and 5 years after. It includes the US as a more relevant comparison for Japan given that it was more of a mature economy than a developing one. We have graphed each countries debt to GDP build up in the 15 years prior to show the familiar pattern forming in China.

As shown in Figure 1, Japan ended its transition spectacularly when it let asset bubbles form; and South Korea damaged its transition when it let its corporate sector get overleveraged in the pursuit of growth, leading to it being sucked into the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

As shown in Figure 1, Japan ended its transition spectacularly when it let asset bubbles form; and South Korea damaged its transition when it let its corporate sector get overleveraged in the pursuit of growth, leading to it being sucked into the Asian financial crisis of 1997.

There is of course no guarantee that history will repeat itself, but the chart shows three countries on three different economic journeys that all faced significant issues when private sector debt grew too quickly. Similar patterns existed for Spain leading up to its 2009/10 economic crisis and Mexico prior to its 1995 Peso crisis.

With both Korea and Japan, it was the lack of financial supervision that allowed the crises to build. Arguably, this is no different to the US led global financial crisis, but in the case of the US, the economy was already mature and investor confidence well established, so the crisis was short lived. In the case of Japan and Korea, the damage to consumers and investors alike was longer lasting, and arguably permanent in the case of Japan.

But, it is not too late for the Chinese government to avert the crisis. It’s always dangerous to say it is different this time, but in China’s case there are some genuine differences. Their economic and political model enables far more central control than full capitalist democracies can afford.

The question is more about willingness to accept slower growth in the short term in exchange for reducing the risk of following Japan. Their handling of the asset bubbles in equities and property is so far a good example of how this central control can be an asset for China, and therefore for the world.

China not showing same central control and strength on corporate debt so far

But corporate debt, particularly amongst state owned enterprises in steel, coal and property represents the best example of how it can be a major liability. In 2014, they committed to reducing the overcapacity in steel and coal, and the excess inventory in third tier city property in 2014, but then caved in early 2016 when economic growth slowed.

Much of the debt stimulus in early 2016 went to these industries, re-opening previously mothballed factories and mines. This is not the sign of a government committed to long term stability; more the sign of a government focused on its short term scorecard.

China has achieved much of its economic miracle firstly from the convergence phenomenon and then since the GFC, by applying debt stimulus to sustain convergence. Now they need to remove the debt stimulus gradually enough so as not to cause instability, but soon enough to avoid the problems faced by Japan and South Korea. A finely balanced operation, on which we are all dependent.

Australian investors should hope for smooth transition, but plan for risk of a crisis

Australian investors, more so than any other western country, critically depend upon China’s ability to navigate this transition. It is not just the mining, tourism and education industries; our property and therefore banking sectors are now intrinsically dependent upon capital flows from China.

A slow landing in China will see those capital flows continue and probably grow, benefiting the whole economy. But a hard landing will see capital suddenly stop, which would be very damaging to property markets in particular, and then by virtue of our national obsession with property, consumer confidence and then the economy as a whole.

In this series, we will look at the most recent data out of China but from a longer term viewpoint to let the reader form their own view of the outlook for China, and therefore what risks they might face as an Australian investor. Specifically we will look at:

- Whether the Chinese government can effectively stimulate the economy with debt or if they are running out of runway;

- The rapid decline in private investment in China in contrast to the remarkable growth of the Chinese consumer; and

- What the ongoing downward shift in exports from and imports to China means for Australia.