The approach used by the ABS to measure unemployment is outdated and misleading, particularly as a guide for investors looking for direction about the RBA’s likely next moves

The approach used by the ABS to measure unemployment is outdated. Last week’s headline unemployment rate of 5.6% was misleading as it hides the truth of the employment market in Australia today:

- Full time jobs are actually lower than at the end of 2015

- 14% of the workforce is working less than they would like to

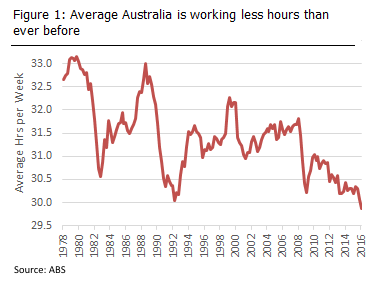

- The average hours worked by those in the labour force just dropped below 30 hours per week for the first time

To be counted as employed, you need to work as little as 1 hour in the reference week. It does not matter whether you want or need to work more, clock up 2 hours and you miss being counted as unemployed. There are several issues with this approach that I would argue make it outdated and is leading to complacency in those managing the economy and the public in general:

- An economy is at its full potential when every willing worker has as much work as they want. An economy with everyone working half the hours they want to would have an unemployment rate of 0%.

- The rapid increase in workplace flexibility is positive for the economy overall, but a part time job offering half the hours the worker needs is half a job. The unemployment rate effectively counts it as a full job.

Alternative measures of employment

The challenge is, what measure should we use instead?

Figure 1 shows the average hours worked by those in the labour force. It shows unemployment indirectly as the unemployed are included in the labour force and so with zero hours worked, they would bring down the average hours.

Figure 1 shows the average hours worked by those in the labour force. It shows unemployment indirectly as the unemployed are included in the labour force and so with zero hours worked, they would bring down the average hours.

But the problem with this measure is that it is inflexible; if society shifted so that more people wanted to work but only say 20 hours per week, the average hours per week overall would fall. We could have 100% employment but with an average of 20 hours per week if 100% of the labour force wanted 20 hours per week and got that much work.

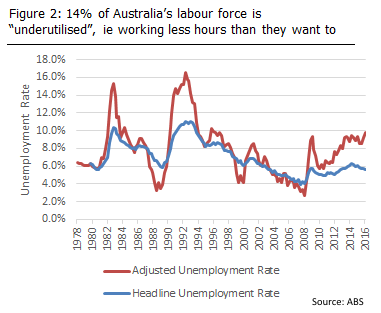

We could adjust the unemployment rate to show how many more people would be unemployed if the average hours per week remained at a constant level, for example the long term average of 31.5 hours.

Figure 2 shows what happens if we do this. The unemployment rate would now be very close to 10%, and higher than any time in the past forty years, other than the early 1980s and early 1990s recessions. As shown in Figure 2, this approach also accounts for overheating economic cycles where the average person is working more hours than usual – the peak of the cycles in 1989, 1999 and 2008.

Figure 2 shows what happens if we do this. The unemployment rate would now be very close to 10%, and higher than any time in the past forty years, other than the early 1980s and early 1990s recessions. As shown in Figure 2, this approach also accounts for overheating economic cycles where the average person is working more hours than usual – the peak of the cycles in 1989, 1999 and 2008.

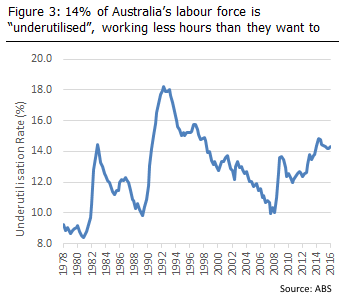

The ‘underutilisation rate’ adds the “underemployed”, those that want more work but can’t get it, to the unemployment rate. The ABS calculates this figure each quarter with estimates monthly, so it is a viable alternative.

It is the percentage of the population that want to work but can’t get the hours they want to. If someone wants to work 20 hours a week but can only find 10 hours per week, it would capture them as “underutilised”. Similarly if someone wants to work full time but can only find a part time role, they would be captured as underutilised.

It doesn’t undervalue part time roles, but it also doesn’t claim that someone working half the hours they need to should be considered as “needing stimulus”.

The unemployment rate is used by politicians to measure their performance in creating jobs, by businesses to assess the economic outlook, and by the RBA to consider whether stimulus, such as a lower cash rate is needed to increase employment growth. The underutilisation rate would be a better measure for all of these purposes than the currently preferred unemployment rate.

The unemployment rate is used by politicians to measure their performance in creating jobs, by businesses to assess the economic outlook, and by the RBA to consider whether stimulus, such as a lower cash rate is needed to increase employment growth. The underutilisation rate would be a better measure for all of these purposes than the currently preferred unemployment rate.

Conclusion

The already measured underutilisation rate is a far more accurate metric when judging the health of the Australian economy, particularly when assessing the prospects for interest rates. As shown in Figure 3, using this metric, the employment market has more underutilisation at the moment than any time other than the 1992/93 recession. Similarly, using the hours worked approach shows the worst outcome on record, and the adjusted unemployment rate has only been worse in full recessions.

Whichever way you look at, the reality of the employment market is very diferent to that suggested by the headline unemployment rate of 5.6%. Employment growth is already weak and still weakening, which will provide plenty of pressure on the RBA to lower rates further in the coming years.