By George Whittle and Henry Stewart

On 7 June 2017, Spanish Bank Banco Popular Español became the first organisation to be bailed in under the Basel III reform, with its contingent convertibles (CoCos) taking the biggest hit

A layperson can’t be blamed for not having heard of Banco Popular Español – for most Australian investors, European banks are not exactly front of mind. However on Wednesday, this Spanish bank became very important. The organisation is the first under the current crop of international banking standards, Basel III, to fold.

Banco Popular has suffered in recent times due to its book of poorly performing loans, which have severely impacted its capital ratios. On 7 June 2017, the bank was put into a resolution scheme with all equity and junior debt written off completely.

This is an excellent example of how a bail in is supposed to work and the protections – or lack thereof – afforded to different parts of the capital structure. From a capital structure perspective, European banks look very similar to Australian banks and, just like the Europeans, the regulator can essentially zero out different parts of this structure that have point of non viability conversion clauses.

In the Banco Popular example, Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1; mostly ordinary shares but also retained earnings and paid in capital) and Additional Tier 1 (AT1; equity like hybrids) were immediately written off. Tier 2 (subordinated bonds) fared slightly better – the banking regulator converted them to ordinary shares, all of which were then forcibly sold to another major Spanish bank, Banco Santander for one Euro. Senior debtholders and depositors were untouched; the senior bonds rallied in price from approximately EUR90c to EUR102c as shown in Figure 1.

Banco Popular Español performance of senior debt versus CoCos

Figure 1

Figure 1

Source: Bloomberg, M&G Investments, FIIG Securities

In theory, how far write offs progress up the capital structure in the event of a bank’s non viability should depend on the size of the problem. The easy route is to say that a country’s resolution authority will consider each distressed bank on a case by case basis and will reflect the difficulties faced. That has been the view of some notable commentators and market participants, but we respectfully disagree.

While failing banks may be insolvent, the trigger for their failure is almost always a lack of liquidity. That is, the ability to meet long term financial obligations is somewhat irrelevant if there are immediate ones. Reducing long term liabilities addresses solvency concerns but has very little effect on liquidity – the coupon cost for AT1 is deferrable and it is marginal for Tier 2. The total magnitude of both pales in comparison to the magnitude of coupon costs for senior debt, due to the difference in volume outstanding.

Given write offs don’t address the immediate problem, there must be another benefit.

In a scenario like this one, it is very difficult to see any capital that can be easily written off being left intact. The benefits are twofold:

- The state of a bank’s assets at a given point in time is complicated to assess. A regulator is likely to err on the side of caution and reduce liabilities by as much as practicable

- The bank purchasing the failed institution has a duty to shareholders to maximize return on equity. By bailing in Tier 2 capital, the regulator makes the acquisition more palatable

Considering the above, it is challenging to comprehend any circumstances where a regulator believes a liquidity crisis is so dire that it justifies the extraordinary step of bailing in capital instruments to cause a coercive equity raising or sale, but isn’t of enough concern to bail in everything possible. In particular, it raises interesting questions about the push for Tier 3 total loss absorbing capital – that being senior debt that can be bailed in.

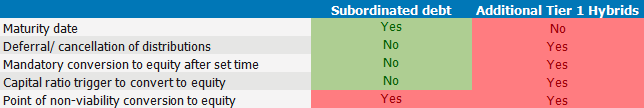

However, this doesn’t mean that AT1 and Tier 2 should be viewed equally or price similarly during the ordinary course of business. There are material differences between the two security classes, which justifies different pricing. They are both valuable sources of bank funding that can be relatively more or less attractive at different points in time as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Source: FIIG Securities

Investors should understand that their recovery, given default, only differs slightly – only one of them will get to frame that single Euro.

We encourage clients who hold bank securities – ASX listed hybrids, subordinated debt, and senior bonds – to continually assess their positions and speak to their dealer if they have any questions. For investors who do seek to make a change, we continue to see value in switching from bank subordinated debt into Liberty’s three year senior debt.

Glossary

AT1

Contingent convertible capital instruments (CoCos) also known as Additional Tier 1 (AT1), are meant to be loss absorbing instruments that convert to equity if needed to protect the survivability of a bank

Basel III

Basel III is a comprehensive set of reform measures, developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, to strengthen the regulation, supervision and risk management of the banking sector.

Point of non viability

Point of non viability, the point at which regulators decide a bank is no longer able to function. To count towards regulatory capital ratios under Basel III, subordinated bonds must be written down to zero or converted to equity when the trigger is hit.

Subordinated debt

A bond or loan that ranks below senior debt, loans and creditors.

Tier 2 is a contingent convertible capital instrument that is meant to be loss absorbing.

In the event of a wind up (insolvency) of an issuer, subordinated debt is not paid until all senior debt and unsecured creditors are paid first.

Total loss absorbing capacity (TLAC)

The debt or capital available to absorb losses in banks.