We all understand the dependence Australians have on the success of the Chinese economy, but how well do we understand how it is run given the vast differences to our own democratic, free economy system?

China’s Communist Party has a crucial “Congress” where new leaders are elected next month, which will impact the investment outlook for all Australian investors.

Economic data out of China last week pointed to its economy still racing along, despite warnings about the need to slow credit growth. This is not surprising for the simple reason that China’s most important political event for ten years occurs in just a few weeks and that means short term results are going to be put ahead of longer term reforms for now.

China’s credit crisis and relevance to Australians

China’s economic health is critical for Australia to maintain its current economic growth and for property and equity values. Current Chinese economic data shows continued health, but a large part is attributed to Chinese state owned enterprises borrowing to invest in fixed assets such as property, factories and infrastructure.

Many economists, including me, believe that China is now investing far too much in unproductive assets such as residential property that will take years to sell. In 2009, promoting economic growth by encouraging credit growth was a sound policy but each year that China artificially inflated its own economic growth using credit, assets were being built that had weaker and weaker payback prospects. While the building of assets creates economic activity that creates GDP growth today, credit has to be repaid, and when there isn’t the income coming from the assets to pay for it, GDP growth tomorrow will suffer.

This phenomenon is not new to economists. Several economies have gone through this cycle of becoming addicted to GDP growth and then when the natural growth of the economy starts to peter out, they increasingly encourage credit growth to keep the party going longer. Japan and Norway in the mid-1980s, Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea in the late 1990s, and US and Europe in the 2000s – all these economies were overextended through excessive credit, and all ended in credit crises that created economic hardship.

China’s excess credit growth now exceeds the levels reached in Japan, South Korea, the US and Europe at the peak of their pre-crisis credit expansions. There is of course no reason to believe that China absolutely must follow these examples, but it does certainly mean that investors need to be wary and ensure that they are not excessively exposed to a credit crisis in China.

Next month’s Congress will decide who runs the economy

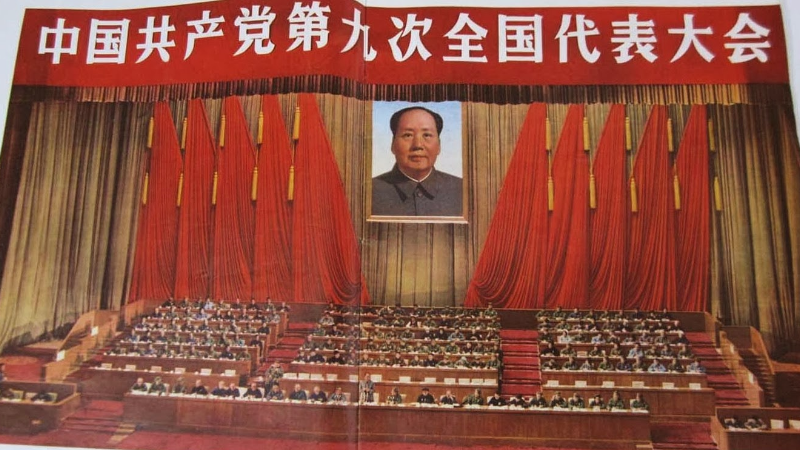

The National Congress of the Communist Party of China kicks off in just five weeks. That Congress, occurring every five years but with the more important election agenda occurring in the odd years such as 2017, is as close as China gets to a democratic event. It includes an election of the General Secretary, or the leader of the Communist Party. As China only has one political party, the General Secretary is the most powerful office in the country and is also President of the People’s Republic of China and head of the Central Military Commission.

Figure 1: How the Chinese leadership team is chosen

Source: Stanford University, Bloomberg, New York Times, BBC

Source: Stanford University, Bloomberg, New York Times, BBC

Other elections include the 200 member Central Committee, the 25 member Politburo and the most powerful positions of the Communist Party, the seven member Politburo Standing Committee. As Figure 1 shows, this is the majority of the decision makers for the Chinese economy.

Aside from not being a democracy, the major difference between China and most western countries is that those chosen to run key departments are considered experts in that subject area. While in a democracy we get to choose our representatives, we have no way of choosing who becomes the Treasurer, the Minister for Human Services or any other key position. Purely from an economics standpoint, there are some strong arguments for the Chinese model.

Those elected into the Politburo typically come from a leadership position as a province chief (from an area other than their native province), but mostly after serving on the Central Committee first. So right now, hopeful candidates to the Central Committee and to the Politburo are managing economic results more closely than any time in the past ten years.

So imagine if our economic data was compiled by organisations controlled by people wanting to impress their peers for a once-in-a-decade election. Would we be sceptical about the data presented? That’s an easy ‘yes’, so we would be unlikely to invest on that basis. Anyone that buys Chinese equities, AUD or iron ore off the back of recent data is, by the same token, buying a lie.

Conclusion and investment ideas

Data out of China is difficult to rely upon at the best of times. Right now with the Congress looming, it is even more so. The intuitive direction for the Chinese economy once this Congress is out of the way is for it to deleverage. They cannot continue to build debt at the current pace. But we know that investment markets often buy or sell on short term news, so there is an opportunity over the next few weeks that the market gets overly optimistic about China’s prospects, and therefore Australia’s prospects, by putting too much faith in the data and news from China prior to the Congress.

Beyond the Congress, when this deleveraging occurs, hopefully in a controlled, steady fashion, it will be the steel and property sectors in particular that will contract. This will impact the AUD and iron ore prices. A controlled deleveraging, as opposed to a bursting of China’s credit bubble, will lead to a moderate decline in iron ore and a 2-3 cent decline in the AUD. A less controlled deleveraging will result in larger falls, but more importantly, add significant global volatility.